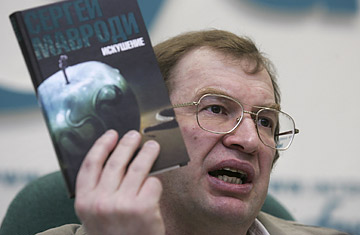

Sergei Mavrodi, founder of the MMM financial pyramid scheme

How to describe Russia's most famous charlatan, Sergei Mavrodi? Take the swindling power of Bernie Madoff, combine it with the hypnotic creepiness of a midnight televangelist, wrap it in a math teacher's wardrobe, and you'd be pretty close. During the 1990s, Mavrodi's crude financial pyramid scheme, MMM, cheated millions of Russians out of their savings, turning the ex–night watchman into a symbol of that decade's shameless brand of capitalism. But now, three years after serving out his sentence for fraud, Mavrodi has returned to his old hustle, and the authorities can't seem to do anything about it.

On Jan. 11, Mavrodi launched a new pyramid scheme, MMM-2011, which uses pretty much the same trick that got him sentenced to 4½ years in prison the last time. It asks investors to buy his so-called MMM Dollars — which he playfully calls "candy wrappers" — and wait for him to assign them a new value twice a week on his blog. He said he expects their value to grow by 30% per month for "pensioners and invalids" and 20% for everyone else, but stressed that this was only his opinion: "I could be wrong," he said on his blog.

That kind of candor is what sets Mavrodi's game apart from your average pyramid scheme. Unlike the original MMM, which Mavrodi passed off as an upstanding financial institution with retail locations that sold its shares (complete with Mavrodi's picture on the front), the new MMM is more up-front. "This is a pyramid," Mavrodi said in his appeal to the nation on his blog. "It is a naked scheme, nothing more ... People interact with each other and give each other money. For no reason!" Somewhat less believably, he added, "I'm not getting a penny out of this. I'm simply showing the way."

On the following day, Mavrodi claimed that he had been overwhelmed by requests from investors. The outrage from the authorities is pouring out just as fast. But there's a problem: no official can name which part of Russia's porous financial legislation Mavrodi has violated. So instead they have been suggesting that an act of selective justice — or a Kremlin fiat — could be used to shut Mavrodi down. Back in 1994, when Russia's legal system was still a post-Soviet wreck, President Boris Yeltsin had to issue a special decree to stop MMM's wildly successful ad campaigns.

This time Vladimir Zhirinovsky, the leader of a nationalist party, has called for a court to ban Mavrodi from conducting any financial transactions whatsoever — which would be a clear violation of his civil rights — while the Kremlin's financial ombudsman, Pavel Medvedev, said in a live radio interview on Thursday that he would "try to influence prosecutors" to intervene. Any such measures, however, would run counter to a central pledge of President Dmitri Medvedev's administration — to ensure equal justice for all — and Mavrodi has been quick to exploit this dilemma.

On Thursday, Mavrodi posted videos on his website appealing to President Medvedev and Prime Minister Vladimir Putin to make sure that he "be judged under the regular laws of Russia, like any other citizen." Then, as an extra layer of defense, he began to act like a victim of government hounding, a ploy that harks back to his early days.

In 1994, when the state tried to imprison him on charges unrelated to his first pyramid scheme, Mavrodi portrayed himself as a crusader against state tyranny and persecution — a move that got him elected to the parliament that year. The government then had to go to the extra trouble of revoking his parliamentary immunity before it could bring fraud charges against him in 1996. And even then, many Russians still believed that the state was just trying to steal Mavrodi's fortune.

Andrei Kashevarov, the deputy head of one of Russia's main financial regulators, FAS, is now leading the efforts to stop Mavrodi and says the state has to tread carefully this time. He admits there is no case against Mavrodi yet, and says that even warning the public to stay away from the scheme would be premature. "There is a problem with giving warnings, because they could be construed as state intrusion into [Mavrodi's] entrepreneurship," Kashevarov tells TIME. "So before warning anyone we have to become convinced that this is socially dangerous, and we can only do that once we analyze this scheme."

On Jan. 21, FAS will host an "expert council" of regulators and law-enforcement officials to figure out what legal weapon they can use against Mavrodi. But the danger for Russia, as it is for much of the world, is that financial tricksters are good at outwitting the law. Roland Nash, a 16-year veteran of the Russian financial market and now manager of the fund Verno Capital, says Russian regulators are at a particular disadvantage in trying to build airtight rules against these kinds of schemes. "They don't have the institutions or the history to build that kind of framework," he says, while pointing out that even in the West people like Bernie Madoff were getting away with fraud on an unprecedented scale.

So as Russia goes after one of its wiliest ex-cons, it may need to get creative with the use of its existing laws to stop more of its citizens getting burned when the pyramid collapses.