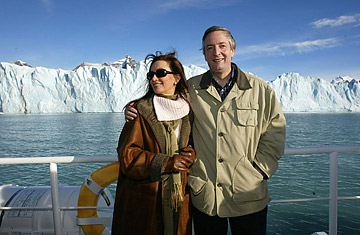

Nestor Kirchner and his wife Cristina Fernandez, pose for photographers before the Perito Moreno glacier 17 in Calafate, southern Argentina, May 2003.

When Néstor Kirchner, who died Wednesday morning from a heart attack at age 60, became President of Argentina in May of 2003, one of Latin America's largest economies was in frightening free fall. During the crisis' darkest days, in late 2001 and 2002, the peso had lost 75% of its value against the U.S. dollar, the nation had defaulted on almost $100 million of debt and an enraged middle class saw its bank accounts frozen to halt runs on banks. Amidst the often violent chaos, Argentina had tangoed through five presidents in less than 17 months.

Kirchner, an obscure provincial governor from Argentina's southern Patagonia region, finally restored economic order. His self-described "heterodox" mix of Peronist populism and fiscal discipline baffled international lenders (and infuriated some) but stemmed the crisis and produced some of the region's highest growth during his four years in the Casa Rosada. In 2007 Kirchner stepped aside so that his wife, Cristina Fernández, could run for President.

She won, but Kirchner remained Argentina's most important politician, widely considered the power behind her throne. He was expected to run again next year as Fernández in turn stepped aside for him — part of what fans and foes alike called the couple's "shared presidency." As a result, Kirchner's sudden death, at their weekend home in the Patagonian town of El Calafate, is almost certain to throw Argentine politics into turmoil. Says Fernández biographer Sylvia Walger, "The most likely scenario is that his death will unleash a battle between heavyweights" in his center-left Peronist party "to gain the kind of influence over her that her husband had."

When Kirchner ran for the presidency in 2003 he was a political dark horse, little known outside his province of Santa Cruz, where he'd been a popular governor since 1991. But it was there that he began to define his more centrist populism. Though he was critical of the shift by then President Carlos Menem, also a Peronist, to free-market neoliberalism, Kirchner fostered increased capitalist growth in Santa Cruz while promoting social programs that narrowed the province's enormous wealth gap.

That experience bore fruit for Kirchner after he defeated Menem for the presidency in 2003. Even though his victory was hardly a mandate — he scored only 22% of the vote in the first round and then won the runoff only because an aging Menem withdrew — a combative and sometimes authoritarian Kirchner strode into Buenos Aires wielding an unorthodox economic plan. He refused to follow International Monetary Fund guidelines, but he succeeded in restructuring Argentina's debt (though many investors weren't happy to see their bonds reduced to about a third of their value in the process) and, in a political flourish, paid off its IMF debts in 2005.

To keep Argentina's crisis-angry population of 40 million governable, Kirchner took populist measures such as renationalizing certain utilities and setting export limits on essential goods. But rather than blow the windfall Argentina was suddenly experiencing from the global price boom for commodities like meat and soybeans, he replenished the country's foreign reserves and encouraged new industries like biotechnology. Kirchner, a foreign policy leftist who kept the U.S. and George W. Bush at a cool distance — leftwing, anti-U.S. President Hugo Chávez was a key ally — called his middle path "a kind of globalization that works for everyone and not just for a few." It was a philosophy other Latin leftists, like Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, have also had success with.

By 2007, Fernández, whom Kirchner had met at law school, was a Senator — and was often being compared to another powerful Argentine female, Eva Perón, or "Evita," the wife of 20th-century strongman president Juan Perón. Riding Kirchner's popularity, she won the presidency that year in a landslide. But her own presidency has been a rockier outing — in part because her husband's policies also created a big jump in inflation — evidenced by the beating the Peronists took in the 2009 midterm elections, when they lost their majority in Congress.

Since then, the party has split into pro- and anti-Kirchner factions, and many wonder if Fernández can hold it together. Political columnist Rosendo Fraga even wrote in the Buenos Aires daily La Nación on Wednesday that "the absence of Kirchner feels like the President is missing, and one almost wants to ask how the Vice President will react. Up to the last moment, he made it clear to all that he was the one in charge and not his wife, and she never rejected this notion publicly."

But even some Fernández opponents call that an exaggerated perspective. Says former Buenos Aires Governor Felipe Sola, a Peronist who may now face Fernández in next year's presidential election as a breakaway candidate, "Cristina will withstand the shock of her husband's death. Even though I'm an opponent, I don't agree with those who believe she can't chart her own course. She is a strong woman and I believe she will find her own way ahead."

At age 57, Fernández at least doesn't have the health issues Kirchner dealt with in recent years. Two artery blockages this year, the latest in September, made his death less than a surprise. Despite his condition, he continued to attend public rallies and accompanied Fernández to the recent U.N. General Assembly in New York. But now the world will watch to see how well Argentina recovers from the end of its "shared presidency."

With reporting by Tim Padgett/Miami.