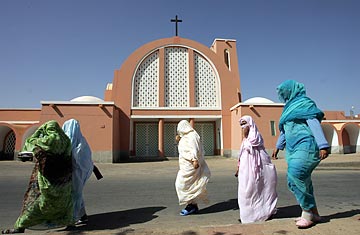

A church in Morocco

March 8 is not a day that Chris Broadbent will soon forget. The preceding weekend, gendarmes entered the Village of Hope, a Christian-run orphanage in Morocco's Atlas Mountains where Broadbent, a New Zealand native, worked as a human resources manager, and began questioning children and staff. At first, he and the other foreign workers were assured that the interrogation was routine. But as it dragged on, the questions turned to subjects like 'How do you pray?' and the police began searching homes on the compound for children's Bibles. On Monday morning, after being held in a separate room from the orphanage's 33 children, Broadbent and his 15 colleagues were summarily deported from Morocco, accused of illegally proselytizing for their faith.

"Most of the couples were there as foster parents and had raised these children since infancy," Broadbent says. "When they were told that their parents had to leave, it was chaos — the kids were running after any adult they could find, and just holding on. It was the most devastating thing I've ever seen."

The Village of Hope deportations are part of what appears to be a widespread

crackdown on Christian aid workers in Morocco. An estimated 40 foreigners

— including Dutch, British, American and Korean citizens — have been

deported this month, including Broadbent and his colleagues. Among them were

an Egyptian Catholic priest in the northern city of Larache and a

Korean-born Protestant pastor in Marrakesh who was arrested as he led

services in his church. And this past week, authorities searched an

orphanage founded by American missionaries in the town of Azrou called The

Children's Haven. Salim Sefiane, a Moroccan who was raised at the orphanage

and is still in touch with workers there, said the officials interrogated

the orphanage staff and asked children as young as 8 years old to

demonstrate how they pray. No action has been taken yet against the

orphanage's workers, Sefiane said.

(See below for a video of the workers at the orphanage being deported.)

The large-scale deportations came as a surprise in a nation that is among the most liberal of Muslim countries. Although trying to convert Muslims to other faiths is illegal, Morocco tolerates the presence of other religions and is home to a number of churches and synagogues. "There are several things about this that are really striking," says Spanish journalist Ignacio Cembrero, who has written several books about the country. "There have been occasional deportations of people accused of proselytizing before, but never so many at once, and they've never expelled a Catholic before. And for the police to enter a church on Sunday, during services, to arrest people? Absolutely unprecedented."

According to the Moroccan government, the deportees all broke the law, using their status as aid workers to cover their proselytizing. "They are guilty of trying to undermine the faith of Muslims," Interior Minister Tayeb Cherkaoui said in a press release.

But were they? Broadbent denies the charges. Part of his job at the Village of Hope was to ensure that staff members understood the rules prohibiting proselytizing, and he notes that all the orphanage's children received instruction in Islam. "We weren't teaching Christianity in any formal way," he says. But asked if reading the Bible to Muslim children constitutes proselytizing, he said, "We understood that it wasn't. And in any case, the authorities have always known that these children were being raised in Christian families." In fact, Village of Hope had been operating for 10 years and had received "institutional" status from the Moroccan government this year — a designation meaning it meets government standards. Many of the other deported Christians had also been in Morocco for extended periods of time. So why were they evicted now?

Christopher Martin, a pastor since 2004 at the Casablanca International Protestant Church, says he's talked to three different people with connections "high up in the Moroccan government" and heard three different explanations for the action. But one common thread, he points out, is that the officials leading the crackdown — the Justice and Interior ministers — were both appointed in January. That suggests to many Christians in Morocco that the officials were eager to quickly make a mark on the political landscape with an initiative likely to have broad popular support.

Although the Moroccan government has in recent years dramatically reformed its family law to better protect the rights of women and has even sponsored programs to train women as Muslim preachers, it has also proven responsive to an increasingly religious public. In recent years, alcohol licenses have become much more difficult to obtain, and last September, for the first time, police in various cities arrested Moroccans who were eating in public during the fast period of Ramadan. The action prompted a formal complaint from the international organization Human Rights Watch.

Aaron Schwoebel, the information officer at the U.S. embassy in Rabat, says that the Moroccan government has told the embassy there will be more deportations, including other Americans. He said the government did not indicate when. "We urge the Moroccan government to act in accordance with its highest traditions of tolerance," Schwoebel says, "And respect the human rights of the members of these religious minority communities, including those of our own citizens."

Now living in Spain after the gendarmes escorted him and his family to a departing ferry in Tangier, Broadbent hopes for the same thing. The last he heard, the Village of Hope children were still living at the orphanage, but he suspects they may soon be sent to other homes. "We'd like to open a dialogue that would lead to reuniting these families," he says. But in the meantime, he can only wonder about the meaning of it all. "Is this an isolated incident?" he asks. "Or is Morocco steering away from its tolerant past?"