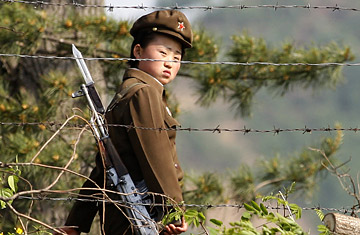

A female North Korean soldier looks out from behind a barbed-wire fence around one of the country's camps

Some say the same whims that informed their long sentence could work in the favor of Ling and Lee, who were reporting for Al Gore's Current TV when they were detained. North Korean activists like Seoul-based Kim Sang Hun, who has interviewed nearly two dozen former prisoners, says the journalists "won't see the real conditions" in the North's prison system because even Pyongyang knows the situation in the country's penal system is something to be ashamed of — a humiliating condition that the Americans would only bear witness to once they were released. Kim thinks the journalists probably will not endure corporal punishment and could, in fact, be out of North Korea soon, depending on the political climate between Pyongyang and Washington. "There's no rule of law, so the sentence is meaningless," says Kim. (See pictures of North Korea's secrets and lies at LIFE.com.)

The Americans are likely to be separated from the general prison population and may be secluded from the true hardships of penitentiary life. That doesn't mean it will be easy. North Korea's prisons and camps are scary places, the horrors of which are gradually becoming known to the world. Indeed, Kim and others believe that while the two women will be treated differently, they will still probably be sent to a regular prison — called a kyohwaso, or reformatory — rather than a prison for political prisoners, where conditions are relatively better. Kyohwaso life is extremely harsh: scholars estimate only 50% of prisoners survive their first year. One of the first accounts of the North Korean prison system, a 2000 memoir called The Aquariums of Pyongyang, tells of routine torture and deprivations on par with those of Nazi concentration camps. The book's author, Kang Chol Hwan, was imprisoned in the Yodok concentration camp at age 9 for 10 years with his family. He suffered starvation and disease and was forced to attend public executions. "I attended some 15 executions during my time in Yodok," he wrote. Kang was imprisoned at the camp because his grandfather had been sentenced for suspicious behavior. "It's guilt by association," says Tim Peters, a Christian activist living in South Korea who has helped numerous North Korean defectors find safe havens in other countries.

Shin Dong Hyuk, a 27-year-old who is reportedly the only living former prisoner to escape a North Korean prison camp, also wrote a recent book about his experiences, Escape to the Outside World. Shin says he was born and raised in a camp about 55 miles north of Pyongyang and like many prisoners witnessed routine atrocities, including the execution of both his mother and brother. Before his escape in 2005, Shin was tortured at least twice, once for accidentally dropping a sewing machine in the garment factory where he was forced to work at the camp. He also watched a prison guard beat a small girl to death for hiding a few grains of wheat in her pocket. (See pictures of North Koreans at the polls.)

Kim Tae Jin, president of a Seoul-based organization called the North Korean Gulag Shutdown Movement, spent four years in Yodok for trying to escape the country. "I was always hungry and cold," he says, recalling life in the camp. He remembers scavenging for dead rodents and snakes to eat. "When I found one, that would be a good day," he says. At his camp, it "was normal for the prison guards to be cruel. No one had hope or cared about anything," says Kim, who was finally released. The camps' pervasive sense of hopelessness is a common theme woven through many defectors' accounts, says Peters. "Any sense of justice is completely absent," he says. "People often don't even know what their crime is. It is really grim stuff."

These stories come from North Korean survivors who did not have the potential advantage of the world's attention as they served out their long and difficult sentences. Lee and Ling have the Obama Administration moving on their behalf; the White House has already urged North Korea to release them "on humanitarian grounds." Sources knowledgeable about North Korean politics and prisons say Pyongyang will not allow the high-profile prisoners to starve to death, die of disease or endure torture. Small comfort. In any case, since their detention in March, the journalists have been visited by representatives of Sweden's embassy in Pyongyang, and over the weekend, some news outlets reported that former U.S. Vice President Gore may also be trying to go to North Korea on their behalf. How quickly those outside influences will make their way inside North Korea's camps, however, remains to be seen.