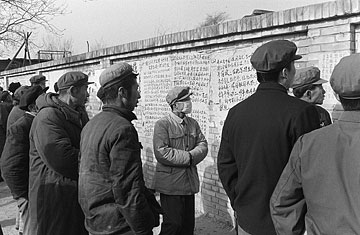

Beijing pedestrians view posters on a city corner that would become known as Democracy Wall on Dec. 5, 1978

A group of prominent Chinese scholars, lawyers and former officials issued a manifesto this week calling on the Communist Party to back wide-ranging political reforms including direct elections, a separation of powers and the rehabilitation of people persecuted under authoritarian rule.

"The Chinese people, who have endured human-rights disasters and uncountable struggles across these same years, now include many who see clearly that freedom, equality and human rights are universal values of humankind and that democracy and constitutional government are the fundamental framework for protecting these values," states Charter 08, a 4,000-word document that was posted on a U.S.-based, Chinese-language website on Dec. 9. (See pictures of life on the fringe in China.)

An English translation by China scholar Perry Link was subsequently posted on the website of the New York Review of Books. In his introduction, Link notes that the document takes its title and inspiration from Charter 77, which was issued in January 1977 by Czech and Slovak intellectuals calling for human rights in Czechoslovakia and abroad. Like its historical predecessor, Charter O8 recalls moments throughout Chinese history when intellectuals felt an obligation to speak out against shortcomings of the state, such as the 100 Days Reform of 1898, when scholars pressed the crumbling Qing dynasty to reform.

"The Chinese government's approach to 'modernization' has proven disastrous," the charter states. "It has stripped people of their rights, destroyed their dignity and corrupted normal human intercourse. So we ask: Where is China headed in the 21st century? Will it continue with 'modernization' under authoritarian rule, or will it embrace universal human values, join the mainstream of civilized nations and build a democratic system? There can be no avoiding these questions."

Many of the rights it calls for are already included in China's constitution, but they are widely ignored and abused, and advocating them in public can be seen as a perilous challenge to the Communist Party. The document calls for an entirely new constitution for China, as well an independent judiciary, direct elections, freedom of religion, speech and assembly, and the right to form independent political parties.

How the government reacts to the document — and the people who signed it — remains to be seen. Pu Zhiqiang, a prominent human-rights attorney in Beijing, says he signed the charter because he supports its emphasis on freedom and democracy. "Not only do I approve these ideas, I believe the Chinese Communist Party and the Chinese government have no reason not to approve them," Pu says. "These are not bad ideologies. The charter does not advocate violence, nor does it aim to destroy the current social order."

More than 500 people joined Pu in signing the document. Bao Tong, a deputy to Communist Party Secretary Zhao Ziyang, who was purged from the government for his support of the 1989 pro-democracy protesters, is the most prominent former official on the list. It also includes activists such as Liu Xiaobo and Ding Zilin, who co-founded the Tiananmen Mothers group after her teenage son was killed in the 1989 crackdown. Several prominent lawyers and writers who are actively working and publishing also signed, giving Charter 08 more clout than it would carry if it were the work of only politically isolated dissidents. "It seems like a varied bunch, and I think the Internet helped bring these people together," says Joshua Rosenzweig, a Hong Kong–based official with the Dui Hua Foundation, a human-rights group. "It's not simply what many people call dissidents. There are a number of well-known liberal intellectuals and lawyers."

The declaration was released during a period of sensitive anniversaries. It comes 60 years after the signing of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which Chinese scholar P.C. Chang helped draft, and 30 years after Deng Xiaoping launched the economic liberalization that would transform China into a capitalist powerhouse. It was also 30 years ago that activists in Beijing posted signs on a Democracy Wall calling for political reform, including electrician Wei Jingsheng's declaration that Deng Xiaoping's campaign for Four Modernizations in agriculture, defense, industry and technology was meaningless without a fifth modernization, democracy. "It's quite a moving document ... as far as setting out clearly the aspirations for China's future in a way that is highly principled and idealistic, [but] doing so in a way that's not attacking the current government and not attacking the Communist Party," says Rosenzweig. Though, he admits, "there's always a danger that it will be read that way." (Read TIME's Man of the Year article on Deng Xiaoping.)

In an interview published Tuesday by the state-run Xinhua news service, Wang Chen, director of the State Council Information Office, said that over the past 30 years, Chinese citizens have enjoyed improvements not just in their material welfare, but also in civil and political rights. "It is not exaggerating to say that China has made historic progress in human rights and that China's human-rights conditions are in the best historical period," Wang said.

The advocacy group Human Rights in China reported that on Monday night, the evening before the document was published, Beijing police raided the houses of two signers, activists Liu Xiaobo and Zhang Zhuhua, and took them into custody. Zhang was released after 12 hours, the group said, but Liu remains in detention. Pu, the lawyer, said Beijing police followed him on Dec. 9 and asked him to report his whereabouts on Dec. 10. That day marks the anniversary of the 1948 adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights by the U.N. General Assembly.

Elsewhere in the city on Wednesday, dozens of petitioners protesting causes such as wrongful terminations and illegal confiscation of property gathered outside the Foreign Ministry office, according to reports. After a short while, police broke up the rare demonstration, corralled protesters onto a bus and drove them away from the government offices.

— With reporting by Lin Yang