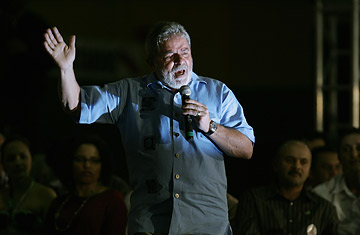

Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva

With their endless strings of pearly beaches, heavenly climate and sensual bossa nova culture, Brazilians regard themselves as uniquely blessed. So last fall, when massive oil reserves were discovered off the coast near Rio de Janeiro, President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva saw it as further proof of a celestial bond. "God," he gushed, "is Brazilian."

That kind of good fortune, divine or not, has helped Lula, 62, a former union leader, become the country's most popular President in half a century. Even without the oil find — which could make Brazil one of the world's largest crude producers — the economy is growing vigorously, and the nation's notorious social inequality is receding. What's more, Brazil is flexing a newfound diplomatic clout as the hemisphere's first real counterweight to the U.S. (Lula led the creation of a bloc of developing nations, the G-20, to thwart U.S. and European hegemony in global trade talks.) "I believe implicitly that Brazil has found its way," he told TIME in a rare interview at the Planalto presidential palace in BrasIníciolia.

When he addressed the United Nations General Assembly in New York City Tuesday morning, Lula hoped to retire the old joke that Brazil is the country of the future and always will be. Instead, he told his peers among the world's leadership that his country is finally realizing its potential. ("We'll be one of the six biggest economies in the world within 10 years," he boasts.) And he argued that Brazil deserves a permanent seat on the Security Council.

That may be a dream too far, but many in the audience will have acknowledged that the bearded, gravelly voiced President has been a revelation. When he was first elected in 2002, many U.S. experts on Latin America worried that he and his leftist Workers Party would trash Brazil's economy by pursuing socialist and populist policies. But Lula stuck to the market-oriented fiscal reforms of his predecessor, Fernando Henrique Cardoso. Those policies, plus a windfall from high global prices for Brazilian products like soybeans and steel, helped Lula tame the country's notorious hyperinflation and create a boom — growth will be 5% or more again this year.

In truth, Lula has no more problem with being called a capitalist than he does with being branded a socialist. "Let the theorists write their theses; it's called doing things right," says Lula, who disdains academic policy labels. It's about "allowing the rich to earn money with their investments and allowing the poor to participate in economic growth."

Remarkably, Lula has managed to steer Brazil between the Scylla and Charybdis of the right-wing Bush Administration and the left-wing Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez, whose clashes are rocking Latin America. Lula, in fact, is one of the few leaders both Bush and Chavez will listen to. "I joke with them and tell them their fight is very weird," Lula says, "because oil makes them so dependent on one another."

The breach between Washington and Caracas matters less to Brazilians than the huge chasm between the nation's rich and poor. Lula, who as an impoverished kid shined shoes on the streets of São Paulo, has pumped some $100 billion into anti-poverty projects like Bolsa Familia (Family Purse), which provide everything from rewards for poor families who keep their kids in school to financing for small farmers and entrepreneurs. As a result, 52% of Brazil's 180 million people now occupy the middle class, up from 44% when Lula took office.

As Lula enters the homestretch of his presidency — it ends in 2011 — many of Brazil's oldest problems remain unsolved. Chief among them is its education system, which despite increased funding remains a dysfunctional shame. There's also rampant corruption, exorbitant taxes, Amazon deforestation and one of the world's most wasteful public bureaucracies. Lula, who many Brazilians hoped would tackle those plagues more forcefully, blames "a [political] structure that has been there for centuries" but which "we are trying to dismantle." To do that in the two years he has left, however, may require more divine intervention.

(See photos of Pope Benedict XVI's trip to Brazil here.)

(See TIME's pictures of the week here.)