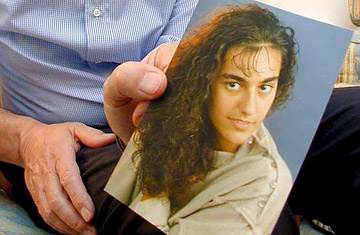

Giuseppe Englaro poses with a picture of his daughter Eluana, who has been in an irreversible coma for the past 16 years.

The questions that drove the Terri Schiavo debate were universal: life and death; man, God and science. But the battle to remove Schiavo's feeding tube after 15 years in a vegetative state — her husband Michael made that decision against the wishes of Schiavo's deeply religious parents — was also a uniquely American drama of fiery Florida preachers, New York talk show hosts and Washington judges and politicians.

Now Italy is embroiled in its own version of the Schiavo saga after a judicial panel ruled in favor of a father who wants to cut off life-support to his daughter, who has been in a coma since suffering irreversible brain damage in a 1992 car accident when she was 20. Though there is no intra-family battle over Eluana Englaro's fate, the case contains the same mix of legal appeals, religious activism and philosophical ponderings. Local newspapers have been filled in recent days with smiling photographs of the now comatose patient before the car crash, and details of her current condition: she breathes on her own, and opens her eyes each morning, but is unconscious and immobile.

Naturally, this drama has its own uniquely local elements that may (or may not) help make more sense of the universal stakes in play. The Italian twists to the storyline include bottles of Ferrarelle and San Pellegrino mineral water placed outside the central Milan cathedral as symbols of the nourishment that many believe she should continue to receive; a public letter from the country's equivalent of Elvis Presley; the die-hard right-to-die Radical party rallying support for the family's choice to let their daughter die; and, of course, the best-known and most looming presence of all in these parts: the Vatican.

Pope Benedict XVI, who is currently visiting Australia for World Youth Day, has not addressed the Englaro case specifically. But his lieutenants were quick to respond after the Milan appeals court ruled last week that, in the absence of a living will, Englaro's "presumed desire" to not continue living by artificial means can be deduced from hearing from her loved ones. Monsignor Rino Fisichella, the influential president of the Pontifical Academy for Life, called the decision "de facto euthanasia." Another top Vatican bioethicist, Monsignor Elio Sgreccia, who'd spoken out in the Schiavo case, accused the Milan court of "interrupting a life, [which] is never within man's authority."

The Vatican is coming off a bruising public battle in the euthanasia arena: Piergiorgo Welby, a paralyzed muscular dystrophy victim from Rome, was denied a Catholic funeral in December 2006 after the right-to-die advocate convinced a doctor to unplug his respirator.

Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi hasn't commented on the Englaro case, but a top conservative ally, Italian Senate President Renato Schifani, introduced a motion to see if the court overstepped its authority. Italy does not have any right-to-die or living-will laws on the books.

Beyond legislative action, the case has generated a huge public reaction: Giuliano Ferrara, a well-known atheist newspaper editor who now regularly sides with the Vatican, called on Italians to bring bottles of water to the Duomo of Milan to protest against the possibility of cutting off nourishment — which hundreds continue to do. The full and half-full green and clear bottles of different sized bottles have turned into a makeshift altar outside the famous downtown cathedral. The Milan daily Corriere della Sera published a front-page open letter Wednesday from Adriano Celantano, Italy's legendary singer and showman. While offering Englaro's father sympathy, he ultimately urges him to follow the Gospel. "Maybe what Eluana needs" writes Celentano, "is her father's conversion so that the departure from this world happens spontaneously and without any interruption. Or even that she wakes up." So far, the family appears willing to wait the 60 days allowed for an ultimate legal appeal before the feeding is interrupted. In the meantime, the drama — and hard questions — will continue.