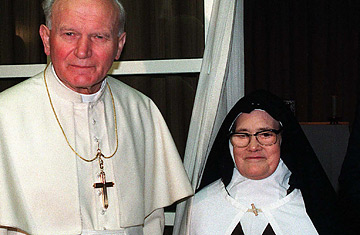

Sister Lucia with Pope John Paul II in 1991

The answer is that to the men now running the church, Sister Lucia meant a great deal. She was the longest-lived of three children to whom an apparition of the Virgin Mary appeared in 1917 in the Portuguese parish of Fatima. And, as Vatican Secretary of State Tarcisio Bertone makes clear in his upcoming book, The Last Secret of Fatima (May, Doubleday) she was the key human figure in a drama that eventually transformed the very nature of John Paul II's image of himself, and of his papacy. Lucia's superstar days may have waned in the memory of post-Vatican II American Catholics, but for people like Bertone and Pope Benedict XVI, who made the journey with the late John Paul, she remains an important symbol.

The story of Fatima began in 1915, when three shepherd children were first visited by what they thought was an angel. By 1917, a figure who identified herself as the Virgin appeared to them, eventually delivering a message for humankind. The children became a focus of massive interest, and in October of that year, the Virgin's presence seem to be confirmed for many others when a crowd of 70,000 — mostly Catholics, some skeptics — saw the sun appear to zigzag in the sky as the Virgin again addressed the children. Fatima almost immediately became a global pilgrimage site.

The message delivered there, however, remained a mystery, because the children refused to reveal the content of the vision they had been vouchsafed. Two of them died in childhood during an epidemic; but in 1941, Lucia, the survivor and by then a nun, released a description of the first two "secrets" from the Virgin that made headlines all over the world. One was a vivid vision of Hell; the other was a prediction that World War I would end, but "if people do not cease offending God, a worse one will break out during the Pontificate of Pius XI." Both would have qualified as prophecy back in 1917. So would an even more topical prediction: that if Russia were not converted to Catholicism, that nation would "spread her errors throughout the world, causing wars and persecutions of the church." From that moment on, Fatima provided mystical expression, and became inextricably entwined, with Catholic anti-communism.

Unlike other famous apparitions of Mary, such as the one at Lourdes, the Fatima message was focused less on holiness than on geopolitics. And in 1952, Lucia sent an even more dramatic "third secret" — rumored among millions of "fatimists" to predict a schism in church or even the world's end — which she sent to Rome in 1952, where three successive popes remained either indifferent, or ambivalent enough to keep it under wraps.

That changed with the 1981 near-assassination of John Paul II by a Turkish gunman. According to The Last Secret, it was while in the hospital recuperating from a bullet that had improbably bypassed his most vital organs that John Paul first asked to be shown Lucia's third secret, and in it read these words: "We saw... a Bishop dressed in white," who reminded the children of "the Holy Father... killed by group of soldiers who fired bullets and arrows at him."

John Paul, aware of Fatima's earlier Russia prophecy and already in 1981 deeply engaged in his own fight against world communism, became convinced that he was the Bishop in white in the vision described by Lucia; that Our Lady had prophesied that he would be shot, but had then turned the path of the bullet at the last instant. In 1982, he made the first of several pilgrimages to Fatima. In 1990, he donated the near-fatal bullet to the shrine there, a gesture that sent fatimists into a renewed frenzy of speculation. In April of 2000, he resolved to respond to their curiosity. He sent Cardinal Bertone to visit the by-then 93-year old Lucia at her convent, and confirm John Paul II's interpretation that he had been the Bishop in her vision — which she did. In May, the pontiff beatified Lucia's two deceased playmates. And in June he made public the third secret, and had it announced that his hair's-breadth escape "seems also to be linked" to it.

As Cardinal Bertone's book helps make clear, the announcement served several purposes. The double beatification and the publication of the third secret endorsed the kind of potent popular piety inspired by Marian apparitions, a trend in popular Catholicism that had gained momentum in the 20th century. But the Vatican response also reined in the flip-side of such enthusiasm: unfettered religious hysteria that can occur when white-hot supernaturalism seems to rupture the staid rhythms of modern institutional religious life.

"Apparitions represent a [necessary] provocation for both theologians and the church," Giuseppe De Carli, whose interview with Bertone is the core of The Last Secret, told TIME. In the book, Bertone seems relieved that all the Virgin's prophecies were now safely in the past tense, and could no longer be seen as portending the world's end: "It's all quite different from the massive carnage certain fevered brains like to imagine taking place," he writes. Then-Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger must have felt the same. In a "Theological Interpretation" that accompanied the publication of the third secret, he suggested that the Bishop in White could represent many popes, and put John Paul's personal pet interpretation as a question: "Was it not inevitable that he should see in it his own fate?" Fatima had simultaneously been reaffirmed, and domesticated.

The centrality of Fatima to the second, "suffering servant" stage of John Paul II's papacy, and his involvement with the two men who would become the Vatican's numbers one and two after his death, may help explain why Lucia's cause has been fast-tracked for beatification. Of course, there are other reasons: Fatima still receives 5 million pilgrims a year, and there is no real downside in pleasing them. And since the Vatican had already carefully vetted the circumstances of Fatima to beatify Lucia's two companions, how much more work need be done to establish the heroic virtue of the third shepherd child?

While the end of the 20th century and the death of Communism may have reduced Sister Lucia's profile among Western Catholics far below those of Mother Teresa or Pope John Paul, the most powerful men in the Catholic Church remember her significance. In a forward to the The Last Secret, Pope Benedict waxes nostalgic about how he and Bertone had "lived" the chapter "that addresses the publication of the third part of the Secret of Fatima in that memorable time of the Great Jubilee of the year 2000." He ends his thoughts thus: "I invoke upon all who approach the testimony offered in this book, the protection of Our Blessed Lady of Fatima." Whatever that means to a new generation of Catholics, it undoubtedly remains deeply meaningful to the pontiff.