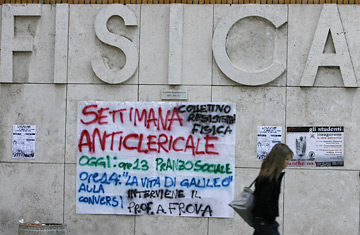

A student walks past a banner reading "Anticlerical Week" in front of the physics department at La Sapienza University in Rome

After three days of rising protests from students and professors, Pope Benedict XVI has pulled out of a long-scheduled visit Thursday to Rome's historic La Sapienza University. The surprise announcement Tuesday afternoon caps a high-stakes academic firefight between fiercely secular scholars and the former professor Pontiff that included a letter from 67 faculty members calling for the cancellation of Benedict's speech.

The Pope's opponents burst out in celebration at the east Rome campus when reached with the news of the cancellation. The Vatican released a statement saying it now viewed the visit as "inopportune" in light of protests they say could damage the Pontiff's image. But by backing out under pressure from his secular foes, the 80-year-old Pope may yet have the last word in this battle over the meaning of "reason" in today's intellectual debate. For the whiff of censorship toward a figure who is welcomed in myriad settings across the world — both for his position and his intellect — may offer ammunition for Benedict's belief that he is something of a "Pope under siege" in the face of the prevailing secular winds of his times.

The Pontiff had been invited by the La Sapienza rector to speak at the annual ceremony to inaugurate the academic year. Over the weekend, unwelcoming banners were already appearing on campus saying "No to the Pope" and "La Sapienza Hostage to the Pope," and several left-wing student groups had promised widespread heckling for Benedict's arrival on Thursday. But perhaps most notable was the professors' letter, which was printed in the Rome daily La Repubblica, calling on school officials to cancel the papal appearance, which they said was "incompatible" with the university's secular mission.

The rector of the 705-year-old university adamantly defended his invitation, which he says he'd do "100 times" over, and Vatican radio warned of "censorship" on the part of the protesting profs. The letter, which was signed by several notable members of the physics faculty, cites a 1990 speech made by Benedict, then the Vatican Cardinal in charge of Church doctrine, describing the Church's 17th century heresy trial against Galileo as "reasonable and fair." The famed Tuscan-born astronomer had been prosecuted for affirming that the Earth was not the center of the universe, but in fact orbited the Sun along with the other planets. Two years after the then Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger's speech, Pope John Paul II expressed regret for how the Church had treated Galileo, whose heliocentric theories have long since been proven correct. The future Pope's words, reads the text of the professors' letter, "offend and humiliate us as scientists faithful to reason and as teachers who dedicate our lives to the advancement and spread of knowledge."

The truth is that neither Benedict nor his secular critics in Rome are all that interested in revisiting the debates of the past; there is plenty of fresh intellectual manna now to tussle over. And Benedict, with his rigorous academic background, is increasingly the focus of the attention. Indeed, the most highly charged moment of Benedict XVI's papacy thus far came in the gracious confines of a German university lecture hall. On that late afternoon of September 12, 2006, the Pope's discourse on faith, reason and violence at the University of Regensberg, where he'd once taught theology, was greeted with long and warm applause by the audience of academics proud that their fellow Bavarian intellectual had risen to the throne of St. Peter. Only later was the lasting significance of the lecture registered: Muslims expressed outrage at references to the prophet Muhammed, and the implication that Islam was predisposed to violence, whereas papal supporters praised Benedict for the frankness of his argument in light of world events.

As opposed to the "inter-civilization" fallout from the 2006 Regensberg address, the battle lines being drawn around La Sapienza were part of an ongoing internal struggle within the West. The public skirmishes occur on the now familiar terrain of bioethics, abortion, Darwin and separation of church and state. But being a lifelong man of study and reflection, Benedict also sees the source for much of the conflict in how ideas germinate and spread on university campuses. Biographers say his experience as a professor during the student upheavals of the late 1960s — where he believed a godless pursuit of personal freedom was spiraling out of control — helped shape his view of contemporary secular culture and the current state of academia.

Forty years later, he appears only more convinced that something is awry. In the same Regensberg lecture that criticized Islam for lacking a fundamental belief in reason, the Pope was also sending a warning to the West that reason itself was suffocating faith and destroying its historical identity. By offering himself up as victim of the La Sapienza professors he can cite further evidence for this argument right in his own backyard.