(6 of 9)

Instead of model settlements, the Polonoroeste project has produced impoverished itinerants. Settlers grow rice, corn, coffee and manioc for a few years until the meager soil is exhausted, then move deeper into the forest to clear new land. The farming and burning thus become a perpetual cycle of depredation. Thousands of pioneers give up on farming altogether and migrate to the Amazon's new cities to find work. For many the net effect of the attempt to colonize Rondonia has been a shift from urban slums to Amazonian slums. Says Donald Sawyer, a demographer from the University of Minas Gerais: "The word is out that living on a 125-acre plot in the jungle is not that good."

The abandoned fields wind up in the hands of ranchers and speculators who have access to capital. Thanks to tax breaks and subsidies, these groups can often profit from the land even when their operations lose money. According to Roberto Alusio Paranhos do Rio Branco, president of the Business Association of the Amazon, nobody would farm Rondonia without government incentives and price supports for cocoa and other crops.

Rondonia's native Indians have fared worse than the settlers. Swept over by the land rush, one tribe, the Nambiquara, lost half its population to violent clashes with the immigrants and newly introduced diseases like measles. Jason Clay, director of research for Cultural Survival, an advocacy organization for the Indians, says that when the Nambiquara were relocated as part of Polonoroeste, the move severed an intimate connection, forged over generations, to the foods and medicines of their traditional lands. That deprived them of their livelihood and posterity of a wealth of information about the riches of the forest. Says Clay: "Move a hunter-gatherer tribe 50 miles, and they'll starve to death."

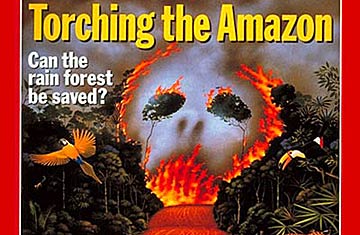

Amid the suffering of natives and settlers, the one constant is that deforestation continues. Since 1980 the percentage of Rondonia covered by virgin forest has dropped from 97% to 80%. Says Jim LaFleur, an agricultural consultant with 13 years' experience working on colonization projects in Rondonia: "When I fly over the state, it's shocking. It's like watching a sheet of paper burn from the inside out."

A similar debacle could occur in the western state of Acre. It is still virtually pristine, having lost only 4% of its forests, but the rate of deforestation is increasing sharply as cattle ranchers expand their domain. Development in Acre has sparked a series of bloody confrontations between ranchers and rubber tappers, who want to preserve the forests so they can save their traditional livelihood of harvesting latex and Brazil nuts. It was this conflict that killed Mendes.