(2 of 9)

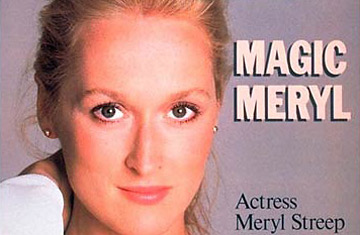

A screenwriter, on the other hand, can give the cinematic Sarah no help at all. She must lance Charles on her own, without the assistance of metaphor, and without a line to speak. Worse, she must do it wearing unflattering makeup, eyes and nose reddened from the rough weather and, perhaps, from weeping. An actress who can manage this adequately is a remarkable technician. One who can do it well is a rarity of the sort who comes along once or twice in a decade. What Charles sees when the cloaked woman turns toward him is an alarming, elemental Sarah who blows through the film like a sea storm, a Sarah who defines the role for all time. Her name is Meryl Streep.

There is a sensible tradition among movie people to say, always, that the actors who are finally cast for a film were the only ones ever considered. This avoids needlessly affronting the actors who were considered but passed over, or admitting that some actors turned down the preferred parts. It also shields audiences from the dampening perception that they are getting second choices. In the case of the extraordinary new film of The French Lieutenant's Woman, however, when Director Karel Reisz swears that when he undertook the project he never thought of casting any other actress as Sarah, the tendency is not only to believe him, but to think, "Yes, of course, that's obvious."

What is remarkable about Meryl Streep's brief film career—Sarah is her first really big role—is that she has brought this same feeling of inevitability even to relatively minor parts. In The Deer Hunter she had only a few important scenes, but it requires a wrenching effort now to imagine another actress playing Linda, Christopher Walken's shy girlfriend. Casual television viewers, who cared not at all that she had made her reputation as a stage actress at the Yale School of Drama and at Joseph Papp's Public Theater in New York City, were struck by her portrayal of a gentile woman married to a Jew among the haunted faces of the Holocaust series. As Woody Allen's lesbian ex-wife in Manhattan, she was chilling and funny, and an exquisite counterpoise to the agitated femininity of Diane Keaton. In The Seduction of Joe Tynan, she was utterly convincing, cornpone accent and all, as the other woman, a Southern civil rights lawyer who falls in love with Alan Alda, a liberal Senator from New York. But to be convincing is merely to be competent, and Streep managed to give enough humanity to a routine role that when the cardboard Senator predictably told her that he was returning to his cardboard wife, viewers worried about what would become of the seductress.

Well before she played Joanna, the wife who walks out on Dustin Hoffman and their son in Kramer vs. Kramer, an astonishing public clamor had set up around this almost gawky-looking blond, all bones and angles. When Kramer opened, the outcry redoubled. Though the script was weighted too much toward sympathy for Hoffman and the boy, Streep brought the film back into balance. By playing Joanna as a woman baffled and hurt not simply by her husband's shortcomings but by her own failures, she gave it a subtlety it would not have otherwise possessed.