(5 of 11)

The senior Sister of the sorority, Exxon, has the highest visibility, not only in OPEC, but in the U.S. as well. As the energy squeeze has worsened, the company has grown so preoccupied with its public image that these days it spends 78% of its $18 million network-TV and magazine advertising budget not on selling products but on promoting its business as one essential to the nation's strategic interests. No longer merely a department title, public affairs affects who is promoted and who is fired within the company, and what actually gets decided. Confesses Chairman Garvin: "I simply do not know of any operating decisions that now get made without lots of awareness of the political and public implications."

Yet the company remains wary and unsure of the public, and in its towering, glass and stone headquarters in Manhattan's Rockefeller Center there is a vague but persistent sense of being under siege.

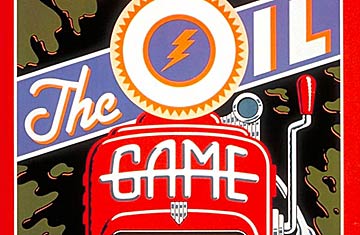

For engineers and chemists like Garvin, who have risen through the company's legendary "Texas pipeline"—from Exxon's sprawling refinery complexes of the Gulf Coast to senior management positions—the Oil Game is no longer very much fun. Hounded by the White House, harassed by consumer and environmental groups, harangued even by OPEC for profiteering, the company has become a target of opportunity for practically every cranky, disaffected group.

Garvin reflects the tensions that plague the company. Tall, blond, looking younger than his 57 years, he nonetheless seems put off balance by the schizoid demands of his position. Is his primary task to make profits for shareholders, who consist not just of the Rockefeller family (they control only about 1% of the stock) but also of union pension funds, investment trusts, and more than 600,000 everyday investors? Or is his main job, as Exxon's advertisements imply, to be a defender of the national security? As Garvin told TIME Correspondent John Tompkins, in an observation that no Exxon chief would have made as recently as five years ago: "I accept that we are in some sense 'different' and that Government is going to have an increasing role in setting the parameters. Our problem is in getting it to act realistically."

Some other Exxon executives are less circumspect. Mused one to Tompkins: ''What we're playing is something like Monopoly, only the board has been changed around, and the dice are loaded. Every time you roll you go directly to jail, and whenever you do collect money it is in rials or yen. Worst of all, you have to play blindfolded while your opponents get to cheat and knock over the table in periodic rages."

Even under the best of circumstances, the challenges that the industry encounters every day create problems of mind-numbing complexity. The volume of oil moved by the companies far exceeds that of any other product or commodity in the world. The more than 380.5 million tons