It was not going well, or at least not as well as Martin Luther King Jr. had hoped. The afternoon had been long: the crowds massed before the Lincoln Memorial were ready for some rhetorical adrenaline, some true poetry. King's task now was to lift his speech from the ordinary to the historic, from the mundane to the sacred. He was enjoying the greatest audience of his life. Yet with the television networks broadcasting live and President Kennedy watching from the White House, King was struggling with a text that had been drafted by too many hands late the previous night at the Willard Hotel. One sentence he was about to deliver was particularly awkward: "And so today, let us go back to our communities as members of the international association for the advancement of creative dissatisfaction." King was on the verge of letting the hour pass him by.

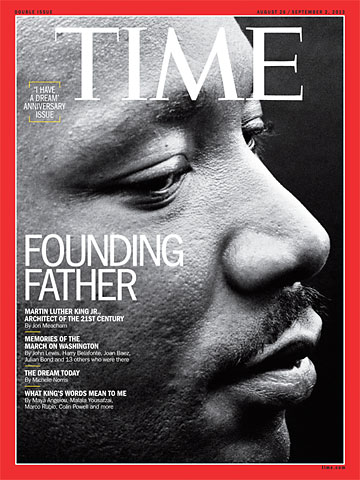

Then, as on Easter morning at the tomb of the crucified Jesus, there was the sound of a woman's voice. King had already begun to extemporize when Mahalia Jackson spoke up. "Tell 'em about the dream, Martin," said Jackson, who was standing nearby. King left his text altogether at this point--a departure that put him on a path to speaking words of American scripture, words as essential to the nation's destiny in their way as those of Abraham Lincoln, before whose memorial King stood, and those of Thomas Jefferson, whose monument lay to the preacher's right, toward the Potomac. The moments of ensuing oratory lifted King above the tumult of history and made him a figure of history--a "new founding father," in the apt phrase of the historian Taylor Branch.

"I say to you today, my friends ... even though we face the difficulties of today and tomorrow, I still have a dream," King said. "It is a dream deeply rooted in the American Dream"--a dream that had been best captured in the promise of words written in a distant summer in Philadelphia by Jefferson. "I have a dream," King continued, "that one day this nation will rise up, live out the true meaning of its creed: 'We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.'"

Drawing on the Bible and "My Country, 'Tis of Thee," on the Emancipation Proclamation and the Constitution, King--like Jefferson and Lincoln before him--projected an ideal vision of an exceptional nation. In King's imagined country, hope triumphed over the fear that life is only about what Thomas Hobbes called the war of all against all rather than equal justice for all. In doing so, King defined the best of the nation as surely as Jefferson did in Philadelphia in 1776 or Lincoln did at Gettysburg in 1863.

I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia, sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood.

I have a dream that one day even the state of Mississippi, a state sweltering with the heat of injustice, sweltering with the heat of oppression, will be transformed into an oasis of freedom and justice.

I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character...

I have a dream today.