(2 of 7)

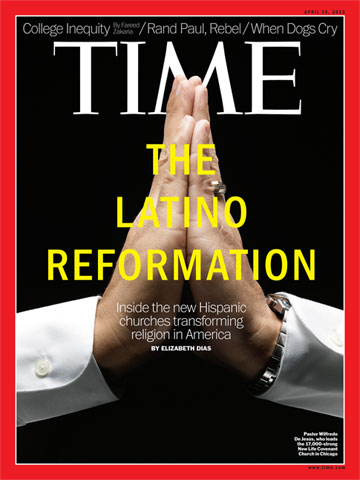

The Latino Protestant boom is transforming American religious practices and politics. Christianity Today, the country's leading evangelical magazine, is preparing to publish in Spanish this year. Record labels in Nashville are beginning to sign Spanish Christian-music groups. Seeing its once solidly Catholic Latino faithful shift to Protestant churches, the Vatican made a bold counterstrike in early March when it named Argentine Cardinal Jorge Bergoglio as Pope--the first Latin American Pontiff and a priest blessed with an uncommon feel for the common man. Meanwhile, the Southern Baptist Convention, the largest evangelical denomination in the U.S., hopes to make a place for these new believers, setting a goal of 7,000 Baptist Hispanic churches by 2020. Today they count 3,200, but the convention's statisticians believe the real number may be larger.

If the numbers are fuzzy, that's in part because Latino congregations are often designed to be hidden. Many start as basement prayer gatherings. Others meet in storefronts. They are often more likely to have a YouTube channel or a Facebook group than a website. Sometimes the only clues that these congregations exist are the dozens of small plastic yard signs that pop up every Sunday to guide the pilgrims. Once you start looking for them, you see them everywhere--on street corners, in yards, on the lawns of other churches. I found signs for Primera Iglesia Bautista Hispana de Maryland in Hyattsville, Md.; Iglesia de Dios del Evangelio Completo in Adelphi, Md.; Iglesia Pentecostal La Gloria de Dios; and Centro Mundial Evangelico in nearby northern Virginia.

These iglesias, or churches, are different in kind as well as in number. Latino Protestants are more likely to get up and dance in church than to fall asleep there. Ushers stand armed not with service bulletins but with Kleenex boxes and folded blue modesty cloths to cover women when they faint in God's presence. The intercessionary prayer list includes typical petitions for healing and comfort as well as for more earthly needs--Samuel's papi has been missing for a week; Maria's cousin needs immigration papers; Ernesto's friend is facing jail time. Richard Land, a former president of the Southern Baptist Convention's religious-liberty commission, told his pastors four years ago to ignore the Latino reformation at their peril: "Because if you left [Washington, D.C.] and drove all the way to L.A., there wouldn't be one town you'd pass that doesn't have a Baptist church with an iglesia bautista attached to it. They came here to work, we're evangelistic, we shared the Gospel with them, they became Baptist."

The evangélico boom is inextricably linked to the immigrant experience. Evangélicos are socially more conservative than Hispanics generally, but they are quicker to fight for social justice than their white brethren are. They are eager to believe in the miraculous but also much more willing to bend ecclesiastical rules to include women in church duties and invite other ethnic groups into their pews. The new churches are in many cases a deliberate departure from the countries and the faith their members left behind--but they don't look or sound anything like the megachurches of the U.S. Evangélicos are numerous and growing fast. And they are hiding in plain sight.

A Reformation in Maryland