(3 of 4)

Great Britain's Office for National Statistics added four questions about well-being to its largest ongoing household survey last year--including "How happy did you feel yesterday?" and "How satisfied are you with life nowadays?"--at a cost of $3.2 million annually, about 1% of the agency's budget. The new questions were derided by critics as a frivolous expense in a time of austerity, but Prime Minister David Cameron, a longtime champion of happiness research, stood firm. "He took some political risks to support it," says Nic Marks, founder of the London-based New Economics Foundation's Centre for Well-Being. The new data will give Britain's policymakers a more complete picture of how the country's citizens are faring, Marks says. "Most people feel disconnected from the dominant economic indicators."

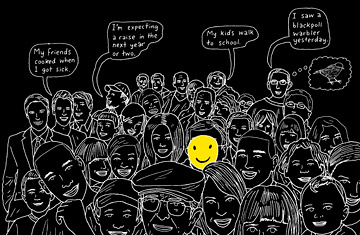

Screening for Happiness

Once countries start measuring well-being, it isn't clear how they should use the data. In Edmonton, the new well-being index is intended simply as another data point to guide long-range strategic planning. At most, "we start to pay attention to inequality of well-being," Anielski says. In the U.K., the modest hope is that well-being measures will creep into the national debate about unemployment and income. "It will start to earn its keep, but that's a slight unknown," says Marks.

That's why in the U.S. well-being indicators have yet to take hold at the federal level. Steve Landefeld, director of the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, acknowledges that GDP's shortcomings are significant: it does not reflect growing inequality, and as the housing bubble showed so dramatically, it doesn't do much to warn about future economic trouble. "We think it's rather urgent" to fix those inadequacies, Landefeld says, but he doesn't see the need for a well-being indicator. The precursor to GDP was devised during the Great Depression to give the President a clear measure of economic health that would respond directly to government intervention. When interest rates fall or infrastructure spending rises, GDP moves in turn. Well-being indicators, as Bhutan's GNH experts admit, aren't very input sensitive and don't move much over time. For policymakers, Landefeld says, "I don't know how useful they are."

Bhutan's solution is to turn GNH principles into a policy-screening tool to achieve that elusive ideal of sustainable economic development. This effort is still in its infancy, but eventually every significant decision by Bhutan's government will go through a GNH filter--a set of questions that force policymakers to consider, for example, whether a new tax or public-works project will affect ecological diversity, decrease stress levels in the population or encourage physical exercise. Bhutan is doing a total review of its mining policy using the GNH screening tool to come up with better bidding processes, regulations and revenue agreements that will minimize corruption and environmental damage. "Environmentally, it's quite a big challenge," says Sonam Tshering, Bhutan's economic-affairs secretary. "We have to be mindful of future generations. But we also realize that minerals are a resource that needs to be used for the country."

Thinking Local