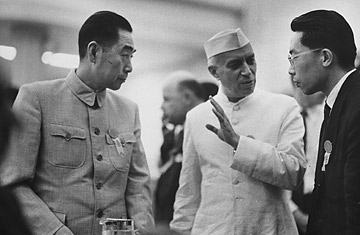

India's Jawaharlal Nehru (center) using interpreter to speak with China's Chou En Lai (left) at the Bandung Conference.

Earlier this year, my family and I were staring at a fearsome Aztec frieze in Mexico City's Museum of Anthropology when an elderly janitor approached. He wanted to know where we were from. "India," we said. Immediately his lips curled into a smile. India, he expounded, led the way. It had a socialist past, stood up to imperialism and offered hope to anticolonial movements. My rudimentary Spanish couldn't keep up with the rest, but he slapped his chest when saying the name of Jawaharlal Nehru, the first Indian Prime Minister. Indira Gandhi, Nehru's daughter and also a Prime Minister, was, he said, like "mi madre."

We were taken aback, but his feelings aren't that surprising. While it's hard to imagine most Mexicans these days referring to Gandhi as their mother, the janitor's affection for India was not an aberration. Indeed, such dreamy-eyed solidarity once shaped the whole worldview of an earlier generation living outside the global north.

In the West, people look back at the latter half of the 20th century and see only the binary conflict of the Cold War, a clash between capitalism and communism, liberal democracy and totalitarianism. But it was always far more complicated than that: most of the world was still emerging from the shadows of empire and the legacies of racism and foreign exploitation. Fledgling nations wanted little to do with the two nuclear-armed superpowers of the day.

The Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) — a bloc of countries trying to chart a path free from the influence of both the U.S. and USSR — was founded in 1961 on that spirit of independence. At NAM's peak, its members ranged from Indonesia to Yugoslavia to Argentina. Its pro-poor, antiwar politics would lead to the bolstering of institutions such as the U.N.'s atomic agency and its development program. Few statesmen stood taller in this project than Nehru — a suave, Cambridge-educated lawyer who, as India won its liberty in 1947, spoke famously of that moment when "the soul of a nation, long suppressed, finds utterance." He went on to inspire fellow third worldists from Africa to Latin America.

But that was then. In the last week of August, as heads of state and dignitaries from some 120 nations gathered under NAM's umbrella in Tehran, there was little room for nostalgia. With the Cold War over, NAM is almost always dismissed as a fusty, pointless relic. The bloc is, in some respects, a failure; as a body representing the global south, it was too weak and fractured to stave off the 1979 Soviet invasion of Afghanistan or the U.S.'s first Persian Gulf intervention in 1990. After spending decades calling for peace and disarmament, NAM's core members now rank among the world's leading weapons purchasers. The socialist bonhomie of NAM's founders has given way to the cold-blooded imperatives of the BRICs. Even in India, some of New Delhi's elites speak of Nehru's internationalist moralism as a naive, self-defeating embarrassment.

That NAM even reached international front pages recently was less a result of its continued relevance and more because of its host. Iran has assumed the rotating three-year mantle of NAM leadership, much to the chagrin of American and Israeli hawks seeking to raise international pressure on Tehran's nuclear program. The U.S. State Department sounded notes of outrage over the Islamic Republic's human-rights record, urging U.N. Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon not to attend. But that call went unheeded; no U.N. chief has missed a NAM summit since the organization's inception.

Instead, as the U.S. grumbled on the margins, NAM seemed to reflect a new status quo. Egypt's Islamist President Mohamed Morsy jetted into Tehran, in part to push the diplomatic envelope on finding a solution to the bloody conflict in Syria — something Washington has little leverage to achieve on its own. Shrugging off months of American hectoring over his country's ties with Iran, Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh held substantive talks with Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. Chief on the agenda was the countries' shared interest in stabilizing Afghanistan, which will remain a headache for both long after U.S. and NATO troops withdraw at the end of 2014.

"NAM is just a name for regionalism now," says Vijay Prashad, a professor of international studies at Trinity College in Connecticut. "And the future of world politics lies in this regional thinking, not the U.S. State Department." The solidarity of old may be gone, but in its place is something far more real: power.