(2 of 2)

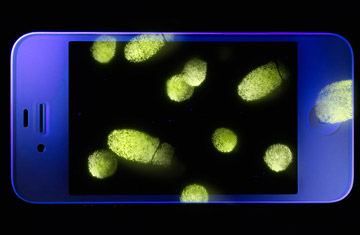

Government snooping is part of the worry. But market demand is driving some of the biggest collectors of data. Mobile advertising is now a $6 billion industry, and identifying potential customers based on their personal information is the new frontier. Last year, reports showed that free and cheap apps were capable of everything from collecting location information to images a phone is seeing. One app with image-collection capabilities, Tiny Flashlight, uses a phone's camera as a flashlight and has been installed at least 50 million times on phones around the world. Tiny Flashlight's author, Bulgarian programmer Nikolay Ananiyev, tells Time that his program does not collect the images or send them to third parties.

In November, news broke that a company named Carrier IQ had installed software on as many as 150 million phones that accesses users' texts, call histories, Web usage and location histories without users' knowing consent. Carrier IQ says it does not record, store or transmit the data but uses it to measure performance. In February, Facebook, Yelp, Foursquare and Instagram apps, among others, were reported to be uploading contact information from iPhones and iPads. The software makers told the blog VentureBeat that they only use the contact information when prompted by users. "No app is free," says one senior executive at a phone carrier. "You pay for them with your privacy."

Many consumers are happy to do so, and so far there hasn't been much actual damage, at least not that privacy advocates can point to. The question is where to draw the line. For instance, half of smart-phone users make banking transactions via their mobile device. The Federal Trade Commission has brought 40 enforcement cases in recent years against companies for improperly storing customers' private information.

Law enforcement is subject to some oversight. Absent an emergency, prosecutors and police must convince a judge that the cell information they are seeking from wireless companies is material to a criminal case under investigation. An unusual alliance between liberals and conservatives is pushing a bill to impose the same requirements for getting cell tracking data as those that are in place when cops want to get a warrant to search a house. Another bill would increase restrictions on what app writers can do with personal information. Cases moving through the courts may limit what law enforcement can do with GPS tracking.

Tech companies are trying to get a handle on the issue. Apple has a single customer-privacy policy. Google posts the permissions that consumers give each app to operate their phones' hardware and software, including authorization to access camera and audio feeds and pass on locations or contact info. The rush to keep up with technology will only get harder: the next surge in surveillance is text messaging, industry experts say, as companies and cops look for new ways to tap technology for their own purposes.