RIMs failure to keep up with Apple has turned it into a tech basket case

Remember when BlackBerry was cool? Just a few years ago, the Research in Motion (RIM) smart phone was the premier mobile gadget on the market and a veritable tech status symbol. The BlackBerry was so ubiquitous among Wall Streeters, corporate types and Capitol Hill staffers that it earned the nickname CrackBerry.

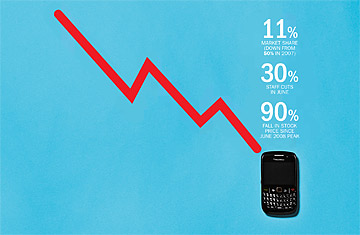

Now it's become the highest-profile tech failure in recent memory. On June 28, RIM reported a $192 million adjusted net loss and said it plans to lay off 5,000 people--about one-third of its workforce. That follows layoffs of 2,000 workers last year. RIM also said its much ballyhooed new operating system, BlackBerry 10, would be further delayed, until 2013.

That will undoubtedly hurt market share, which has already plummeted from 50% in 2007 to just over 11% as customers switched to Apple iPhones and Google Android devices. "Our first-quarter results reflect the market challenges I have outlined since my appointment as CEO at the end of January," RIM's Thorsten Heins stoically told Wall Street analysts. "I am not satisfied with these results and continue to work aggressively ... to implement meaningful changes to address the challenges."

The BlackBerry's decline--and RIM's failure to keep pace with Apple and Google--offers a cautionary lesson about the importance of innovation in a consumer-technology market evolving at breakneck speed. The problems were threefold. First, after coming to dominate the corporate market, RIM failed to anticipate that consumers--not business customers--would drive the smart-phone revolution. Second, RIM was blindsided by the emergence of the app economy, which drove massive adoption of the iPhone and Android devices. Developers have created hundreds of thousands of mobile applications for platforms, fueling rapid innovation in mobile software. Third, RIM failed to foresee that smart phones would transcend mere communication to become full-fledged mobile entertainment hubs. As a result, RIM insisted on producing phones with full keyboards even after it became clear that many users prefer touchscreens, which allow for better video viewing and touch-swipe navigation. And when RIM did finally launch a touchscreen device, it was seen as a poor imitation of the iPhone.

"RIM repeatedly made strategic decisions that were fundamentally wrong," says Silicon Valley--based technology analyst Rob Enderle. "They were either fighting from a position of weakness or they were playing catch-up and letting a competitor dictate their strategy. Never let the other guy dictate your strategy."

It was a failure of vision--and innovation. Whereas RIM saw the BlackBerry as a fancy, e-mail-enabled mobile phone, Apple and Google envisioned powerful mobile computers and worked to make sending e-mail and browsing the Web as consumer-friendly as possible. They also understood that the key to mass adoption would be to build a platform for developers to create applications. In short, RIM failed to heed the example of Apple's late CEO Steve Jobs, who elevated the user experience to Olympian heights.