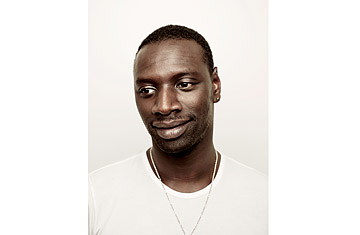

Class Act. France's breakout film star has gone from the banlieues to the big time.

(3 of 3)

Especially amid a stormy election season and economic stagnation, "there is a kind of rupture in French society," says Dominique Sopo, president of SOS Racisme, an antidiscrimination organization in Paris. "A good part of the French population knows nothing about the banlieues where immigrant-origin people live. There is real tension around unemployment and the economic crisis, rooted in a politics that is oriented toward scapegoats." In this poisonous environment, the melting-pot humanity of The Intouchables was a blast of sweet fresh air. "Here was a message that we could all live together," Zekri says. "It clicked with people."

For the people of the banlieues, the rupture that Sopo describes cuts deep. Unemployment in Bondy hovers around 20%, double the national average. Bondy resident Bourimech estimates that only 2 of every 10 people he grew up with have middle-class jobs. According to Mahmoud Bourassi, the director of a community center in Bondy, one of the many challenges that communities in the banlieues face is a tangible psychological alienation from Paris' prosperous zones. "For people here, there is an invisible wall around the pripherique," Bourassi says, referring to the highway that rings Paris' 20 arrondissements. "We talk about people on 'the other side.'"

Sy has passed through that invisible wall. His life has changed markedly since his Trappes days. He now lives in a semirural town on the outskirts of Paris with his wife and four children. To prepare for The Intouchables, Sy spent time back in Trappes, where much of his family still lives. "I thought I'd lost some of those reflexes, the way of talking," he says. "But it was not gone, because I grew up there." He remembers the days before he was a national celebrity, when his wife, who is white, would go alone to scope out apartments for them to rent. "Otherwise we wouldn't get anything," Sy says. "For me, those days are over. But they are not over in France."