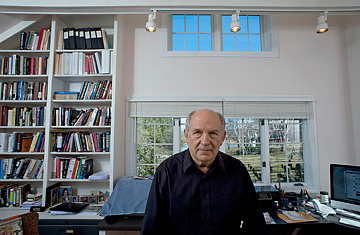

The hermit of Burkittsville. Murray gets perhaps one call a week at his rural Maryland home

(5 of 6)

There is scholarly consensus on several important particulars. Since the 1970s, the gains from the economy have increasingly gone to the very few Americans at the high end of the economic spectrum. It is harder to ascend the class ladder in the U.S. than it is in other advanced industrialized nations, social scientists have found. Isabel Sawhill of the Brookings Institution has argued that this may be due to the comparatively low quality of U.S. public education--a high school diploma simply doesn't give Americans enough to lift them out of the working class. But Sawhill says these trends affect lower-middle-class people of all races: "I don't see any evidence that there is something special happening to white people."

Though he has a Ph.D. from MIT, Murray has never had an academic's instinct for the careful, modest insight. Lawrence Mishel, president of the liberal Economic Policy Institute, showed me two graphs from Murray's book. One, consistent with Murray's argument, shows that the portion of Fishtown suffering from social problems grew alarmingly from the 1970s on. But the other shows that the portion of white Americans who lived in Fishtown dropped precipitously during the same period. Mishel ran the numbers and concluded that the portion of white Americans suffering from the social problems that have Murray panicked has grown very modestly since 1980--from 8% to 10%. "How big a deal is that?" Mishel asks. "Not really a very big deal."

To Mishel and other liberals, the cause of the class crisis in the U.S. is fundamentally economic, not cultural. By focusing on a small core of lazy, uninterested members of the lower class, they say, Murray is drawing attention away from the far broader population of virtuous Americans who cannot support themselves economically. "Do you know how many native-born Americans don't have a high school degree or a GED?" Mishel asks. "It's 5%. We're not talking about a population that is unwilling to educate itself."

Some conservatives have also taken issue with Murray's new book. Frum says the "literary" qualities that led him to admire Murray's work in the past have in Coming Apart displaced serious analysis. "What is really striking in Coming Apart is the adamant shutting of eyes to the most obvious explanation," Frum says. The unambitious culture Murray identifies is, in Frum's view, the product rather than the cause of economic dislocation: "At every point where the questions get hard, the book becomes uncurious. And while it's true that the job of the conservative in the debate is to be less sentimental, this goes beyond unsentimentality. There's a brutal disregard."

When I relay Frum's and Mishel's critiques, Murray says he wishes he'd emphasized the middle class (Middletown) in his book after all. "In Middletown, which is 50% of the population, all these things are getting worse--guys out of the workforce, single-parent homes," he says. "The signs of decay are also present in the middle class. They are not minor. They are substantial."