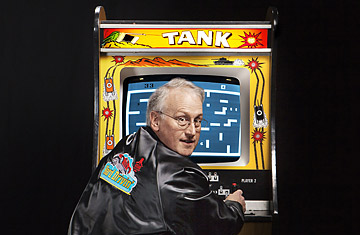

Lyle Rains, Tank. His 1974 multi-joystick game rolled out several sequels. His new target: Angry Birds.

(2 of 4)

In 1983 Atari imploded in what is known as the great video-game crash. Activision and other third-party cartridgemakers cracked the console code and flooded the market with lousy games. Atari, under pressure to produce a blockbuster, started rushing out its own games, most notably E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial, which has come to be known as one of the worst video games ever made. Five million unsold copies were buried in the New Mexico desert. Within 18 months of its release, the debt-laden company was essentially given away.

Mario, Nintendo's mustachioed mascot, revived the North American market beginning in 1985 with quality games and a more sophisticated console. Graphics engines have improved so dramatically since then that virtual worlds are now scarcely distinguishable from the real thing.

Games have followed this steroidal curve as well. Ed Logg, 63, creator of the Atari megahit Asteroids, once described Rip-Off--a classic shoot-'em-up arcade game created by Tim Skelly, his great rival at Cinematronics and now co-worker--as "a poem." Contrast that simple elegance with a celebrated modern shooter: Gears of War, for example. The latest edition of Gears retails for $40, and even an experienced gamer would need 60-plus hours to play it to completion. Yet for all their differences, Gears and Rip-Off fall in the same broad category. The rendering has gotten far better, but the games themselves--the strategies, the action, the backstories--aren't much different from the ones invented decades ago.

The most outspoken critic of the industry's creative stagnation is Innovative Leisure's president, Seamus Blackley, who grew up playing Atari games and, at 44, is young enough to be the son of some of the men his company is reuniting. "Did you ever see the movie Space Cowboys?" asks Blackley, who as an bergeek and former Hollywood agent is big on sci-fi movie references. "NASA had to call up the old astronauts out of retirement and send them back into orbit, because they were the only ones that understood the space station well enough to fix it and save the planet."

In the game world, Blackley is known as the guy who invented the Xbox at Microsoft and later ran the game-talent division at Creative Artists Agency in Los Angeles. After seven years as an agent, Blackley left CAA, reached out to his childhood heroes with an offer of equity and held the company's first meeting--in secret--last July at a hotel in Pebble Beach, Calif., the last town to host Atari's golden era off-site gatherings. Blackley asked each of the coders to show up with an idea for a new game. "We are the Jedi Council of video-game design," he told them.

Atari founder Nolan Bushnell, the man who directed the company's early success from his perch as CEO, is busy with his own start-up but agrees with Blackley's essential premise. "Mobile platforms have reinvigorated Atari-like game play," he says. For evidence, look at Angry Birds. Since Rovio released this addictive puzzle game in 2009, it has been downloaded half a billion times. Zynga, the company behind FarmVille and the other 'Villes, surprised no one when it raised nearly $1 billion in its December IPO.