(3 of 6)

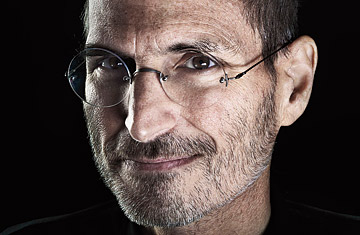

But not so fast; hold your horses: one of the most extraordinary pages in America's corporate history was about to be written. Apple's "mercurial" co-founder Steve Jobs (people like Jobs always find themselves tagged with words like that) was fired from his own company just a year after the Mac's release. In exile he created Pixar Animation Studios and the NeXT computer. His return to Apple in 1997, after it purchased NeXT, is now the stuff of legend. In the design department, Jobs saw the work of a young Briton called Jonathan Ive and asked for a meeting. Ive, underused and ignored for a year, turned up with a resignation letter tucked into the back pocket of his jeans. He left with instructions to unleash his talent. The result was the iMac, an all-in-one computer in a white-and-Bondi-blue transparent housing as far removed from the standard beige box of the day as could be imagined. Ive's next major designs would be the iPod and then the iPhone. Apple's transformation from underdog to the biggest beast in the jungle was under way. And look what's iPadding through the undergrowth toward us now.

The Tools That Make You Smile

In case you've missed the Hoopla, the iPad is a touchscreen slate or tablet computer, about yay big diagonally (where yay = 9.7 in., or about 25 cm), weighing in at just 1.5 lb. (680 g). For Apple, there's something novel about the circumstances of its launch. When the iPhone was released, Apple was a novice underdog entering a smart-phone market dominated by huge, established players like Nokia, Windows Mobile, Palm, Sony Ericsson and BlackBerry. But with the release of the iPad, Apple is an overdog for the first time. The smell of backlash is in the air. The blogosphere and tech magazines are ready to pounce. Apple has overreached itself. What is this device? Who needs it?

I put to designer Ive the matter of all the features that are missing from the iPad. "In many ways, it's the things that are not there that we are most proud of," he tells me. "For us, it is all about refining and refining until it seems like there's nothing between the user and the content they are interacting with."

That's not what he's supposed to say. Tech journalists are obsessed with spec lists and functions. Does it do this? Does it do that? They often look at devices as the sum of their features. But that kind of thinking isn't in Apple's DNA. The iPad does perform tasks--it runs apps and has the calendar, e-mail, Web browsing, office productivity, audio, video and gaming capabilities you would expect of any such device--yet when I eventually got my hands on one, I discovered that one doesn't relate to it as a "tool"; the experience is closer to one's relationship with a person or an animal.

I know how weird that sounds. But consider for a moment. We are human beings; our first responses to anything are dominated not by calculations but by feelings. What Ive and his team understand is that if you have an object in your pocket or hand for hours every day, then your relationship with it is profound, human and emotional. Apple's success has been founded on consumer products that address this side of us: their products make users smile as they reach forward to manipulate, touch, fondle, slide, tweak, pinch, prod and stroke.