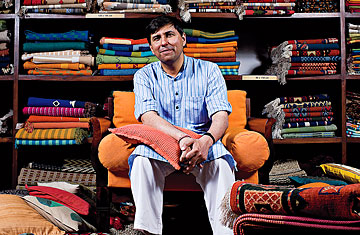

Man of the cloth

Bissell preaches pragmatism

William Bissell inherited a company built on good intentions. His father, John Bissell, went to India in 1958 on a Ford Foundation grant, married an Indian woman and never left. The Bissells started a business exporting handmade textiles, and their company, Fabindia, thrived on sending traditional crafts to the West, just in time for the first wave of baby-boomer bohemian chic.

In 1998, John Bissell died, leaving his then 31-year-old son with a daunting choice. William could let the company coast (the export business was doing well, but handweaving limited the volumes that Fabindia could trade in). Or he could begin selling cheaper, machine-produced cloth, discarding his father's belief in the handmade. Instead, he took a third way. He knit together Fabindia's 40,000 individual artisans into a reliable supply chain and began focusing on the domestic market. Starting with a handful of boutiques, Bissell created a 110-store, $65 million national brand — without straying far from its homespun roots. That makes Fabindia an early beneficiary of the figure upon whom many regional and international economic hopes are now being pinned: the Indian consumer. But when Bissell looks into India's future, he is troubled. "For those of us at the top of the dungheap, the system is working absolutely brilliantly," he says. For everyone else, corruption and the lack of basic public services like water, electricity and education threaten to undo a decade of growth. In a 247-page polemic, Making India Work, Bissell lays out those problems in devastating detail and suggests ways to fix them.

He's not without hands-on experience. Bissell helped found a subsidized school in a Rajasthani village that educates 780 local children, and leads a reforestation project on land nearby. But these and countless other similar initiatives by well-meaning individuals and organizations, he concedes, are mere tinkering. "With our current system of governance, you might be aware of the problem, but there's nothing you can do about it."

Making India Work lays out what he hopes will be a blueprint for action: radically downsizing the national bureaucracy; giving substantive powers to elected neighborhood councils; creating a results-based, incentivized school system under the eye of a "standards authority." A self-described policy wonk, Bissell is clearly more interested in the details of governance than in big ideas (the subject of several recent books by Indian CEOs). "Let's go into the trenches," he says, with the air of the classic patrician philanthropist, "and see what needs to be done."

Some of his proposals seem far to the left of his peers — like setting up a sort of sovereign wealth fund that would use the income from natural resources to fund basic services — but others are refreshingly pragmatic, like a suggestion to measure poverty not by income but by access to water, food, medicine, education and legal rights. "Poverty is the absence of these five things," he says, and indeed there are many whose rising incomes don't reflect the true state of their lives.

They, and increasingly the rest of India's citizens, are simmering with the feeling that things are not right. From public anger over Mumbai's botched response to the 2008 terror attacks, to rising alarm over the Maoist insurgency across a wide stretch of central India, to the frustrations expressed in the biggest Bollywood hit ever — a 2009 film, 3 Idiots, that skewers the grade-obsessed higher-education system — India is a country ready for unflinching points of view. "India is not a poor country," Bissell says. "It's a poorly managed country."

Meanwhile, he is trying to help the community-owned businesses formed by Fabindia suppliers to become self-sustaining. He believes the artisans' future lies in their ability to sell to any company, not just his own. It might sound altruistic, but Bissell is quick to point out that Fabindia won't thrive unless they do. "A lot will depend on what happens to these community-owned companies," he says. For them, as it is for India, good intentions aren't enough.