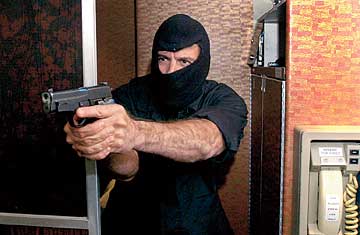

An air marshal wields a pistol during a stimulated hijacking shortly after 9/11.

Three days after the attempted Christmas bombing of Northwest Flight 253, President Obama announced that federal air marshals would ride shotgun on more flights to and from the U.S. Armed, highly trained and unobtrusive, thousands of marshals are currently flying U.S. skies. But whether they can prevent airborne attacks is debatable.

Armed guards have policed American aircraft since the first hijacking of a U.S. jet, in 1961--when a Miami man took over a plane bound for Key West, Fla., and demanded that it fly to Cuba--and subsequent incidents prompted President Kennedy to declare that a "border patrolman" would be placed on a number of U.S. planes. The program was expanded following a flurry of hijackings in the late '60s. In 1970, U.S. Customs sent nearly 1,800 men and women to the U.S. Army's Fort Belvoir for "sky marshal" training. But as the attacks continued unabated, critics slammed the program as ineffective. When airport security measures improved (X-ray screenings of U.S. passengers' bags began in the early '70s), the marshal program deteriorated. After the 1985 hijacking of TWA Flight 847 to Beirut by Hizballah--in which an American passenger was killed--President Reagan expanded the program, swelling the number of marshals to nearly 400.

Hijackings in the U.S. grew rarer in the '90s, and the ranks dwindled again; by 2001, there were reportedly just 33 U.S. air marshals left. Following 9/11, Congress reportedly pushed that number to 4,000, but as the years passed, skepticism returned. One critic, Representative John Duncan Jr. of Tennessee, noted that since 2001, the agency has averaged slightly more than four arrests a year--at a cost per arrest of around $200 million. There were no air marshals aboard Flight 253 on Dec. 25, but that may not have mattered: civilians, after all, took down the would-be bomber themselves.