A rock and a hard place

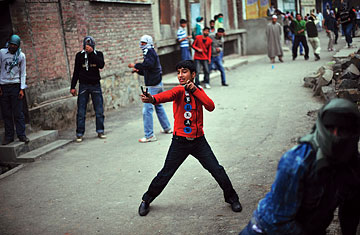

A Srinagar youth readies his slingshot during protests in May

(2 of 2)

The Amarnath controversy alone is not behind the resurgence of local protests against New Delhi — although most of the protest leaders are closely linked with separatists. The more lasting effect has been a pervasive sense of cynicism. The Amarnath killings have been added to a long list of grievances against the Indian security forces, who pretty much run Srinagar on their own — they have wide powers to shoot, arrest and search without fear of repercussions — while Indian and Pakistani politicians and bureaucrats ponder their next moves. The recent rape and murder of two young girls in the town of Shopian, allegedly by Indian soldiers, is the latest outrage. Bashir Dabla, a professor of sociology at Kashmir University who has studied the social impact of the 20-year conflict, says that young people feel abandoned as the issue drags on: "This has given the impression among Kashmiri youth that both these countries are just following their own interests."

That sentiment extends well beyond the young and disaffected. Meraj Gulzar, 36, is the owner of a small information-technology-services firm, one of about 40 companies employing 2,000 people in Srinagar's tiny IT industry. Gulzar wants to bring Srinagar a piece of the economic boom that has transformed so many other Indian cities. "We would like to be as successful as Bangalore, Pune or Delhi," he says. Kashmir has a big advantage — a large population of well-educated but unemployed college graduates whose salaries are far below those in India's established IT hubs. But the state government and the army are virtually Gulzar's only clients; multinational companies are reluctant to outsource work to Kashmir. "Unless and until there is a political solution," he says, "it won't happen."

There's also the psychological impact of living under constant stress, worrying about whether family members will be stopped by security forces. For a visitor to Kashmir, the number of checkpoints and bunkers, all manned by soldiers carrying AK-47s and sometimes just feet apart, is hard to ignore. But more unsettling are the curfews, called during major protests, elections or any time authorities see fit. They are unpredictable, and breaking curfew can mean arrest. So Srinagar tends to empty out after dark; some shopkeepers who used to keep late hours have simply given up, pulling down shutters before 8 p.m.

Talking the Talk

The terms of any likely deal between India and Pakistan are widely known. Earlier negotiations, including so-called "back channel" talks between unofficial representatives of India's Singh and Pakistan's former President, Pervez Musharraf, had moved the two countries toward soft borders, free trade and some kind of joint governance of Kashmir. "Nothing more needs to be done," says Sardar Qayyum Khan, former Prime Minister of Pakistani Kashmir. I heard repeatedly from Kashmiris that an end to the political uncertainty is more important than the details of any proposal. "Anything," says Yasser Kazmi, founder of Myasa Network Solutions, one of Kashmir's oldest IT firms. "Any solution that is acceptable to the people of Kashmir."

Reaching a solution will require overcoming 60 years of deeply entrenched positions held by India's political and security establishment, for whom Kashmir has always been the defining foreign policy issue. Ever since a 1948 U.N. resolution calling for a plebiscite on Kashmir's future — a move categorically rejected by India — any concession is read as an affront to national pride. Pakistan, too, will have to move past decades of mistrust of its larger, better-armed neighbor. The Mumbai terror attacks proved that Pakistan has not let go of its longstanding policy of supporting jihadist groups to destabilize India. Under months of intense international pressure, Pakistani authorities twice detained Hafiz Saeed, an LeT founder who now leads another banned organization, but released him on Oct. 12 citing lack of evidence. Several other suspected top LeT commanders were arrested last December, but none of them have so far been prosecuted. "Without the progress on Mumbai, I don't see very much being possible," says Radha Kumar, director of the Nelson Mandela Center for Peace and Conflict Resolution at Jamia Millia Islamia University in New Delhi.

While there has been no large-scale attack in Indian Kashmir since last November, Indian authorities say that the number of suspected militants trying to cross over from Pakistan has increased noticeably since last year. In late March, Indian troops fought a five-day gun battle in the border district of Kupwara. Eight Indian commandos were killed, as well as 25 suspected LeT militants, but others are assumed to have entered successfully. By late summer, violent attacks returned to the heart of Srinagar after a respite of nearly three years. On Aug. 1, two men from the Central Reserve Police Forces (CRPF) were shot, point blank, in the busy Regal Chowk area. On Aug. 31, two more CRPF men were shot in Lal Chowk in an almost identical attack, this time coordinated with a grenade tossed at the Srinagar police chief's office nearby. September witnessed a further escalation. A Sept. 12 car bomb killed four policemen outside the Srinagar Central Jail; 10 days later, security forces say they killed two suspected terrorists, including a commander of Hizb-ul-Mujahedin, a group based in Pakistani Kashmir. On Sept. 28, CRPF killed three militants; a day later, three CRPF men were gunned down in a market in the town of Sopore.

It could get worse. I ask the young men why they persist if, as they say, the police fire at the known stone throwers first. Most laugh off the question with bravado. But Baig is darkly serious. He will keep throwing stones, he says, "until death." If there is another future for him in Kashmir, the time for it is running out.

— with reporting by S. Hussain / New Delhi, Yusuf Jameel / Srinagar And Ershad Mahmud / Islamabad