(2 of 2)

For black women, hair has classification power (witness the connection Don Imus made between hair and sexual promiscuity when he referred to the Rutgers women's basketball team as "nappy-headed hos"). Just as blond has implicit associations with sex appeal and smarts (or lack thereof), black-hair descriptors convey thick layers of meaning but are even more loaded. From long and straight to short and kinky — and, of course, good and bad — these terms become shorthand for desirability, worthiness and even worldview.

The notion of natural black hair as being subversive or threatening is not new. When the New Yorker set out last summer to satirize Michelle as a militant, country-hating black radical, it was no coincidence that the illustrator portrayed her with an Afro. The cartoon was calling attention to all the ridiculous pre-election fearmongering. But the stereotypes it drew from may be one reason that 56% of respondents to a poll on NaturallyCurly.com say the U.S. is not ready for a "First Lady with kinky hair."

Some black women note that Michelle's choice to wear her hair straightened affirms unfair expectations about what looks professional. On Blacksnob.com a reader empathized with Michelle's playing it safe in the White House and outlined her own approach: "Whenever I start a new job I always wear my hair straight for the first three months until I get health care. Then gradually the curly-do comes out." Another echoed the practice: "I wait about four to six months before I put the [mousse] in and wear it curly ... I have to pace myself because it usually turns into a big to-do in the office."

The amount of money black women spend on hair will be explored in Chris Rock's upcoming comedic documentary Good Hair. "Their hair costs more than anything they wear," he said. Which helps explain the recent news out of Indiana University that black women often sacrifice workouts to maintain their hairstyles.

One might think having a black First Lady who is widely praised as sophisticated and stylish would represent a happy ending to the story of black female beauty and acceptance. Alas, our hair still simultaneously bonds and divides us. "There is no hair choice you can make that is simple," says Melissa Harris Lacewell, an associate professor of politics and African-American studies at Princeton. "Any choice carries tremendous personal and political valence."

Even though I'm biracial and should theoretically have half a share of hair angst, I've sacrificed endless Saturdays to the salon. It is unfathomable that I might ever leave my apartment with my hair in its truly natural state, unmoderated by heat or products. I once broke down at the airport when my gel was confiscated for exceeding the 3-oz. limit.

I'm neither high maintenance nor superficial: I'm a black woman. My focus on hair feels like a birthright. It is my membership in an exclusive, historical club, with privileges, responsibilities, infighting and bylaws that are rewritten every decade.

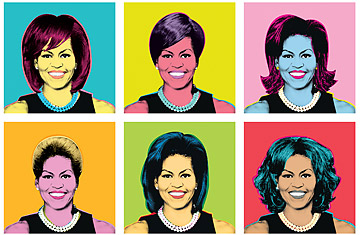

Not once when I've seen an image of our First Lady has it been lost on me that she is also a member. I don't see just an easy, bouncy do. I see the fruits of a time-consuming effort to convey a carefully calculated image. In the next-day ponytail, I see a familiar defeat.

A black family at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue signifies a shattered political barrier, but our reactions to Michelle are evidence that it takes more than an election to untangle some of the unique dilemmas black women face. Thanks to her, our issues are front and center. It feels a lot like when nonblack friends and colleagues ask those dreaded questions that force us to reflect and explain: whether we can comb through our hair, if we wash our braids or locks and the most complicated of all — why it all has to be such a big deal.

Download the new TIME BlackBerry app at app.time.com.