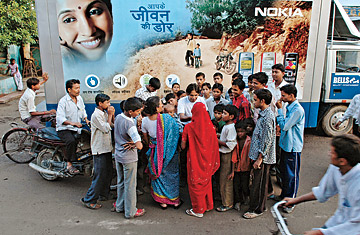

Nokias retail reach across India is a key advantage.

(2 of 2)

Much of Nokia's emerging market dominance boils down to cost management — a crucial advantage when it comes to selling smart phones to price-sensitive consumers in India and elsewhere. Nokia will likely ship more devices worldwide this year than the next three biggest cell-phone makers — Korean rivals Samsung and LG, and London-based Sony Ericsson — combined. Manufacturing on that scale brings enormous purchasing power, making it possible to squeeze the cost of everything from memory chips to plastic casings.

Nokia is also typically more efficient when it comes to how it builds a phone. While an iPhone requires around 1,000 components, Garcha says Nokia's 5800 needs only half that number. "Having an extra 10 or 20 dollars on your bill of materials doesn't matter when you're selling your phone at $600," he says. "Think about making it a smart phone at $100 a few years from now: $20 of cost is 20 percentage points of margin. It actually becomes very important."

But Nokia's real genius is simply in selling phones in more places than any of its competitors. From Indian mountain villages to towns on the dry plains of northern Nigeria, Nokia is everywhere. Supplying the end user with a smart phone in Western Europe and America is typically the job of cell-phone operators who will even subsidize the cost of a device in return for tying a buyer to a monthly plan. Not so in emerging markets, where users typically buy their phone independently. That means manufacturers need their own "very efficient distribution," says Sanford C. Bernstein's Ferragu. "And on distribution, nobody comes close to the strength of Nokia."

Consider India. Years of building its business in the country — the first ever cell-phone call in India in 1995 was carried over a Nokia phone and Nokia-deployed network — has established the company as India's biggest supplier by a huge margin. Nokia devices are sold in 162,000 retailers in India, more than three times the number for rivals Samsung or LG. Although Samsung is investing heavily to catch up, Nokia claims roughly 60% of the Indian market. So ubiquitous are the firm's products that many locals refer to their mobile phone as a "Nokia" even when it isn't. In China, Nokia supplies around 30,000 retailers, far more than its rivals. Across the Middle East and Africa, it has another 120,000 outlets and enjoys a 52% share. (Nokia's slice of the North American market is approximately 10%; in Europe it's more than 40%.)

That kind of presence in emerging markets helps explain why Nokia is blurring the boundary between smart phones and cheaper handsets, and trying to entice customers to trade up. In recent months, the firm has unveiled a slew of devices aimed at developing markets, some costing as little as $60. That might seem a lot to pay for someone earning a few hundred dollars a month, but for many people in places where access to electricity is hit-and-miss at best, a good phone can double as a computer, an MP3 device or even a video player.

Take, for example, Nokia's new 2730 model, which will be available later this year for just over $110. The 3G device might not have a touchscreen or a swish keyboard, but with access to Ovi Mail, Nokia's free e-mail service, it's designed to give thousands of consumers in emerging markets their "first Internet experience," says Credit Suisse's Garcha. Ovi Mail was conceived specifically for consumers with limited PC access, and almost all the 350,000 accounts registered since the service's launch last December have been created on Nokia phones, not on computers. To the company, that bodes well for the future. "We believe giving [consumers] this first digital identity will be a way of getting [them] later on into all sorts of other Internet services," says Alex Lambeek, Nokia's vice president for entry devices. "There's a longer-term thinking behind this."

That outlook no doubt includes extending smart-phone services beyond major urban areas. In rural India, where Nokia controls around four-fifths of the mobile-phone market, according to Bernstein research, locals may not be quite ready for smart phones yet — but they will be. At the Mobile and More outlet in the city of Gwalior in central India, co-owner Gaurav Kukreja's best seller is a no-frills 2G Nokia. But, Kukreja says, "younger people from villages often go to cities to study. They come back well-versed with new technology, and with aspirations. They want the latest ... Its time will come." Nokia execs must hope the same applies to them.

With reporting by Madhur Singh / Gwalior