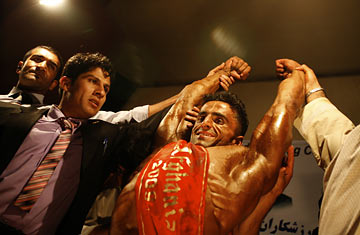

Shuqrullah Shakili, a native of Helmand province, appears moments after he was selected Mr. Afghanistan 2009

It's just past 9 a.m., and people are already filing into Kabul's Park Cinema. The venue's usual fare--shoot-'em-up Bollywood matinees--is popular, but today the films are being pre-empted by a different kind of firepower: the homegrown muscle that makes up the annual Mr. Afghanistan pageant. Backstage, bodybuilders from all over the country crank out push-ups and curl dumbbells for a last-second pump as trainers slap them down with oil and bark encouragement. Armed guards scan the main room for troublemakers as VIPs take their seats in the front row. Behind them, a standing-room-only crowd of some 1,500 people pulses to the reggaeton hit "Gasolina."

Since the fall of the Taliban, bodybuilding has become a national obsession. The Afghan National Bodybuilding Federation has more than 1,000 affiliated gyms across the country, from Kabul to the insurgent-held hinterlands. Billboards of musclebound champions and a shirtless Arnold Schwarzenegger from his Pumping Iron days dot the drab streets of the capital, all smiles and biceps.

Much of the success of competitive flexing is thanks to Bawar Khan Hotak, a former wrestler widely considered the godfather of Afghan bodybuilding. In the 1990s, he and his friends fashioned derelict Soviet tank parts into weight machines, filling oil drums with concrete to make barbells. "We wanted to build something for children here who had nothing to feel good about," he says. "And of course, we loved to exercise ourselves."

During the Taliban days, Hotak helped arrange a bodybuilding competition at Ghazi Stadium, then primarily a site for public executions. While he and other competitors were forced to cover their skimpy shorts by decree of the Taliban, spectators were so impressed with Hotak's showmanship that some threw coins as a sign of their approval--a gesture that angered the ultra-conservative regime, he says, and landed him briefly in jail. After the Taliban fled, Hotak opened Gold's Gym in Kabul, naming it after the original in Venice, Calif., where Schwarzenegger--his hero--trained.

Many have since followed Hotak's lead. Zubair Mohsin, a former Kabul champion, has about 400 regulars who pay $5 a month to work out at his neighborhood gym, Ariana Power. The place stays packed well past 9 p.m. and is equipped with a smoke-belching generator to cope with frequent blackouts. Most of the gymgoers are teenagers who talk earnestly about lifting weights as an alternative to doing drugs. They complain, however, that the financial demands of competitive bodybuilding--for protein powder, personal trainers and steroids, which trainers admit are readily available--are too high.

Afghanistan has even started exporting its talent: Afghan bodybuilders have competed in Singapore, Bahrain and South Korea and won several medals this April at the South Asian bodybuilding championships in Varanasi, India. Even so, the cash-strapped government has done little to promote the sport. In May, the budget for the annual Mr. Kabul competition was slashed amid a dispute between bodybuilders and the Afghanistan National Olympic Committee over the use of scarce funds.