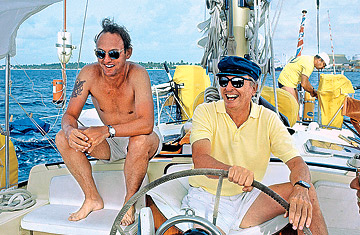

William F. Buckley Jr. and son at leisure.

Once, when he was in college, William F. Buckley Jr. flew an airplane from Boston to New Haven, Conn., at night after a total of an hour and a half of flight training. Buckley also smoked, drank, ate peanut-butter-and-bacon sandwiches and took pills by the fistful. He was a reckless sailor who crossed three oceans--his terrified crews nicknamed him Captain Crunch. He abominated seat belts, and in his later life he developed the unnerving habit of urinating out the open doors of cars going at full speed. Buckley, an icon of the modern conservative movement, died last year at 82 from a heart attack. It's amazing that he lasted as long as he did.

Buckley died just 10 months after his wife Patricia, who was 80. Their son Christopher has written a memoir of that difficult year titled Losing Mum and Pup (Twelve; 251 pages). Christopher--as we will call him to avoid muddling our Buckleys--is best known as a comic novelist (Thank You for Smoking, Supreme Courtship), and in taking on such a tragic, personal subject, he's punching well above his weight class. But his sense of the absurd turns out to be oddly well suited to observing the numerous medical and existential indignities associated with dying, as well as to describing the bizarre, outsize creatures who raised him.

This is not the stuff of recession-era tragedy. Christopher once came home to find his mother in a neck brace: she had curtsied too low to a duchess and caught a heel in her pearls. The Buckleys weren't plutocrats, but William's prodigious output--he could bash out a 700-word column in five minutes flat--and Patricia's inheritance made them more than well off, and the action leaps nimbly from the family's teak-and-mahogany yacht to its 10th century Swiss château to Patricia's memorial service at the Metropolitan Museum's Temple of Dendur.

Both Buckleys had enormous personalities and appetites, which caused them to behave in ways that seem godlike and infantile at the same time. Patricia's major vice was lying: at dinner with a Kennedy, she loudly claimed to have been a juror at the trial of Michael Skakel. (She was not.) William's towering professional achievements and his genuine affection for his son were offset by impatience, impulsiveness, arrogance, gluttony and criminal thoughtlessness. He walked out of Christopher's Yale graduation because he was bored. He blew off his sister's funeral to accept an award.

William Buckley once wrote to an admirer that the secret of happiness was "Don't grow up." He never quite did. This forced his son to grow up all the faster, to the point where he could actually forgive his father's failings or at least laugh about them (though there is an element of Oedipal assassination in this lovingly unflattering portrait). The poetry of Losing Mum and Pup--and it has some--arises from the fact that even extraordinary people are not exempt from the pedestrian, democratic reality of death. When Christopher complains about his father's driving, his aunt says wryly, "Don't you understand? The rules don't apply to him." But in the end, they did.