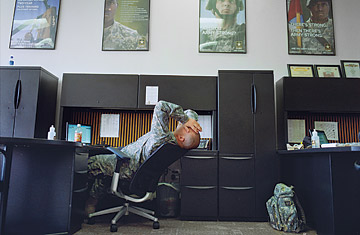

The Nacogdoches, Texas, recruiting office where Larry Flores and Amanda Henderson worked

(3 of 4)

Several months into the job, Aron threatened suicide in front of a girlfriend. After Army doctors cleared him, he returned to work. "For the two years he was in Iraq, I'd turn down the street and be terrified there'd be a car with a set of government plates on it when I got home telling me that he'd been killed," his father says. "Suicide was the last scenario I'd ever come up with."

But that was what occurred on March 5, 2007. In the week before his suicide, Andersson was ordered to write three separate essays explaining his failure to line up prospective recruits. A fellow recruiter later told Army investigators that commanders "humiliated" this decorated battlefield soldier during a training session: "He was under a constant grind — incredible pressure. He just became numb." (See pictures of British soldiers in Afghanistan.)

Andersson, 25, stopped by his recruiting station hours before he died and said he had gotten married that morning to Cassy Walton, whom he had recently met. He seemed in a good mood. "Before leaving, he played a prank on the station commander that made everyone laugh," a fellow recruiter told investigators. But the newlyweds argued that night, and Andersson, inside his new Ford pickup, put the barrel of a Ruger .22-cal. pistol to his right temple and squeezed the trigger. His widow, suffering from psychiatric problems of her own, killed herself the next day with a gun she had just bought.

"That double suicide should have stopped everything," an officer who was in the battalion says privately. Instead, he reports, the leadership in Houston said, "We're just going to keep rolling the way we've been rolling."

Inflated Requirements

The way things rolled in Houston, it turns out, was especially harsh. Until recently, the Army told prospective recruiters they'd be expected to sign up two recruits a month. "All of your training is geared toward prospecting for and processing at least two enlistments monthly," the Army said on its Recruit the Recruiter website until TIME called to ask about the requirement. Major General Thomas Bostick, USAREC's top general, sent out a 2006 letter declaring that each recruiter "Must Do Two." But if each recruiter did that, the Army would be flooded with more than 180,000 recruits a year instead of the 80,000 it needs. In fact, the real target per recruiter is closer to one a month. Yet the constant drumbeat for two continued.

The Houston battalion's punishing work hours were also beyond what was expected. In June 2007, Bostick issued a written order to the 5th Recruiting Brigade and its Houston battalion requiring commanders to clarify the battalion's fuzzy work-hour policy, which could be read as requiring 13-hour workdays. He demanded a new policy "consistent with law and regulation." The brigade and battalion commanders ignored the order.

By mid-2008, a Houston battalion commander complained to subordinates of "getting numerous calls on recruiters being called 'dirtbags' or 'useless' when they do not accomplish mission each month." He'd heard that recruiters who had been promised birthdays or anniversaries off were being "called back to work on the day of the anniversary and during the birthday and/or anniversary party when they already had family and friends at their homes." To improve morale, the battalion's leadership decided to hold a picnic last July 26. "Family fun is mandatory," read an internal e-mail.

Crying Like a Child

Staff Sergeant Flores, a married father of two, who'd looked so haggard last August, was the station commander overseeing the pair of recruiting offices in Nacogdoches. The job required the veteran of both Afghanistan and Iraq to dial into two daily conference calls from his office at 7 a.m. and 10 p.m. "On a regular basis, he would complain to me that the 15 to 19 hours we worked daily were too much," a colleague told Army investigators.

When Flores' station failed to make mission, his superiors ordered him to attend what the Army calls "low-production training" in Houston on Saturday, Aug. 2. "When you're getting home at 11 and getting up at 4, it's tough, but it's the dressing down that really got to him," says a recruiter who worked alongside Flores. "They had him crying like a kid in the office, telling him he was no good and that they were going to pull his stripes."