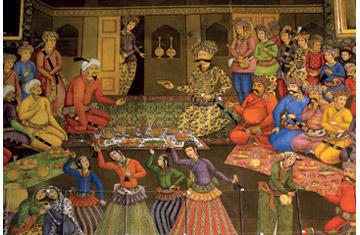

MAN OF THE WORLD: A 17th century wall painting shows Shah 'Abbas welcoming foreigners to his court

(2 of 2)

The legacy of Shah 'Abbas stems from the architecture of his capital, Isfahan. With its mosques, minarets and brightly colored tiles, the city's vast central square remains one of the world's most dramatic public spaces. "A lot of what he did was inspired by the rivalry with the Ottomans," Axworthy says. "It was intended to create an impression of magnificence so that Isfahan was taken as seriously as Istanbul."

The idea of using culture as a way to impress is as relevant today. "For élites and those who visit museums, artistic exchanges can contribute to soft power," says Joseph Nye, a political science professor at Harvard's Kennedy School of Government who defines soft power as "the ability to get what you want through attraction rather than coercion."

It's an idea that's enjoying a resurgence in popularity. Last year, ahead of the Beijing Olympics when China faced renewed criticism over human rights, the British Museum staged exhibitions on the history of the Games in Shanghai and Hong Kong, sending more than 110 invaluable items, including the 2nd century marble statue The Discus Thrower, which the museum had never allowed overseas. And on Feb. 16, the directors of Beijing's Palace Museum and Taipei's National Palace Museum brokered a deal to send Chinese imperial artifacts to Taiwan for the first time in 60 years. In a show scheduled to open in October, the pieces will be reunited with objects taken by nationalists when they fled the mainland after losing China's civil war. Analysts interpret Beijing's conciliatory approach as a bid to improve China's image in Taiwan, perhaps to soften opposition to reunification. Whatever's behind it, Beijing's more amicable stance is welcome news to Chou Kung-shin, director of the Taipei museum. "Cultural exchanges," she says, "are the most convenient and effective way to establish communications across the Strait." (See pictures of the Beijing Olympics.)

There are, of course, limits to the effects of this form of diplomacy. The Shah 'Abbas exhibition isn't likely to convince visitors that Iran should have access to nuclear arms. But in chronicling the nation's former glory, it may help explain why many Iranians feel entitled to them. Curator Canby says there's also a bigger point. "I don't think of it in terms of redressing public opinion," she says. "Museum relationships are based on something other than politics."

That something is an appreciation of beautiful objects and the history they embody, two things curators will go to great lengths to protect. After U.S. troops invaded Iraq in March 2003, looters besieged the country's national museum, stealing 8,000 objects that had come from ancient Mesopotamia. Donny George, the Iraqi museum's former director, phoned from Baghdad and described the situation to a curatorial colleague in London. That curator spoke to MacGregor, who phoned then Prime Minister Tony Blair's culture secretary. A few hours later, U.S. tanks were moving into position to guard Iraq's finest museum. "It was possible entirely because of the long links kept between curators even through the worst moments of Saddam Hussein," says MacGregor. In a world where political relationships can be as fragile as an ancient vase, that's a lesson leaders would be wise to remember.

— With reporting by I-Ching Ng / Hong Kong