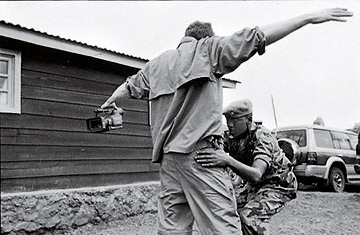

Affleck is patted down before he interviews Laurent Nkunda.

The picture of the eastern region of the Democratic Republic of Congo has grown tragically familiar: a region with great natural wealth, riven by war, racked with hunger and traumatized by a long history of colonial abuse, postcolonial kleptocracy and plunder. In the past 10 years alone, millions have died here, and more die each day as a result of the conflict. Most die not from war wounds but from starvation or disease. A lack of infrastructure means there is little medical care in the cities and none in rural communities, so any infection can be a death sentence. The most vulnerable suffer the worst. One in five children in Congo will die before reaching the age of 5--and will do so out of sight of the world, in places that camera crews cannot reach, deep in a vast landscape and concealed under a canopy of bucolic jungle.

It is common in the West to read about African lives in grim statistical terms, so we've become inured to these huge numbers of deaths. Making matters worse, the conflict in Congo is often seen as a hopelessly byzantine African tribal war, encouraging the damning notion that nothing will ever change. This, of course, creates a sense of hopelessness--and nothing cuts down on humanitarian, foreign and development assistance so much as the jaded diminution of hope. The nation most in need of investment gets the least by the cruel logic that it is the most broken. It is a self-fulfilling prophecy that ultimately fosters indifference in the guise of wisdom.

That should not be the case in Congo.

I've been traveling to Congo since 2007 to learn. TIME has agreed to publish my amateur journalism on the merits of this urgent crisis and on my good luck with photographers. James Nachtwey, the world's finest war photographer, accompanied me on one of my trips, and his extraordinary work fills the following pages.

The warring parties in the east can be distilled into three main groups: the Congolese army; a breakaway faction composed mainly of Tutsis, led by a former general, Laurent Nkunda; and an outlaw militia, the Democratic Liberation Forces of Rwanda (FDLR), led by the same Interahamwe Hutu extremists who committed the 1994 genocide of Tutsis in neighboring Rwanda.

Of late, most of the world's focus has been on the fighting between President Laurent Kabila's army and Nkunda's forces. When I met Nkunda, he made a compelling case for his rebellion, framing it as opposition to Kinshasa's cooperation with the génocidaires of the FDLR and offering a moving history of the persecution of the Tutsi. But like many militia leaders, Nkunda and his men have been accused of war crimes. I met a number of child soldiers who served in his militias, and his soldiers have been accused of participating in massacres in the villages of Bukavu and Kiwanga.