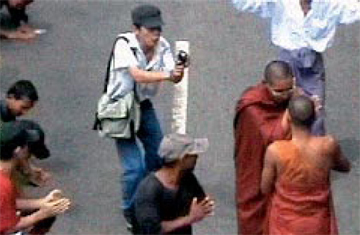

Real or re-enacted? A still from Burma VJ. It's hard to tell which scenes are authentic

When I recall reporting Burma's doomed pro-democracy uprising for TIME in September 2007, one image stands out. Amid cheering crowds, a monk holds aloft an upturned alms bowl to indicate his brethren's refusal to accept offerings from the military. It's a powerful gesture in a devout Buddhist country, but what strikes me is not the monk but the ordinary Burmese holding aloft cell phones and cameras to record his protest. Images like these were then transmitted out of Burma via the Internet, where they were picked up by major broadcasters and shown to the world.

One of those cameras perhaps belonged to a video journalist, or VJ, from the Oslo-based broadcaster Democratic Voice of Burma (DVB), whose courageous work is the subject of Burma VJ, a documentary by Danish director Anders stergaard. It is narrated by Joshua, a soft-spoken 27-year-old who, after being fired from a Burmese government newspaper, joins DVB's small but tenacious team. Founded in 1992, DVB is a nonprofit media organization that broadcasts news in English and Burmese via radio, satellite television and the Internet. Sixty of its 140 staff are undercover reporters in Burma. Despite the risks, and probably because of them too, Joshua's new job makes him feel purposeful and alive. "When I pick up the camera, maybe my hands are shaking," he tells us in the opening scene. "But after shooting for a while, it is O.K. ... I have only my subject in my mind, you know?" After filming a small but near-suicidal street protest, Joshua narrowly avoids arrest and leaves the country. When the monks start marching soon after, he coordinates his colleagues back in Burma from a Thai safe house, ensuring the footage they smuggle out reaches the DVB.

The central event of Burma VJ is the 2007 uprising. "Film them! Film them all! So many! So, so many!" cries one protester into a DVB camera, which then pans upward from the crowded streets to show rooftops and balconies packed with more cheering Burmese. It's moving to watch, not least because we know how it all ended. Within days, perhaps a hundred or more people were killed by the junta and thousands arrested. Those carrying cameras were singled out. (See pictures of Burma's aftermath.)

The footage provided by DVB is edgy, visceral and raw, as you would expect from VJs who must shoot from the hip and run like hell to evade the junta's thugs. In a dictatorship, even the simple task of interviewing a subject is potentially perilous. How can you tell if your subject is an informer? How do you convince them that you're not one? When one of Joshua's colleagues tries to film an early protest march, a monk shoos him away, perhaps suspecting he's a spy. With its haunting score and slick editing, Burma VJ not only captures the fear, paranoia and exhilaration of the undercover reporter, but also gives a bruising idea of how precarious life is for millions of Burmese.

But there's a but. Burma VJ is pitched as a documentary, when it is actually a docudrama relying heavily on dramatic re-enactments. It begins with a disclaimer: "This film is [composed largely of] material shot by undercover reporters in Burma. Some elements of the film have been reconstructed in close co-operation with the actual persons involved." Mixing documentary footage with dramatic reconstructions is said to be a hallmark of stergaard's films. With Burma VJ, that hallmark is a handicap, undermining the film's credibility and dishonoring the very profession its subjects risk their lives to pursue.

No scene is labeled as a reconstruction. Some are convincingly real, yet others are so simply betrayed as re-enactments by their wooden dialogue that soon I began to anxiously question the authenticity of every scene. I felt moved by a sequence showing protesters gathering on a Rangoon backstreet in defiance of the junta. But when I learned that it had been shot from scratch in the northern Thai city of Chiang Mai, I felt something else: manipulated.

The filmmakers will argue that the real issue here is the terrible plight of the Burmese people. In one sense, they are right. In a clever sequence, we are watching the annual military parade when the frame freezes and then quickly rewinds through recent Burmese history. First, it is comic — the regime's troops, marching backward — then tragic. We glimpse survivors of Cyclone Nargis, dazed and clad in rags; refugees fleeing the smoldering remains of houses laid waste by Burmese troops; blood-drenched protesters on the streets back in 1988, when the last democracy uprising was snuffed out and thousands were killed. Twenty years of suffering is compressed into a few searing seconds. But it is still hard to simply recategorize Burma VJ as a well-made docudrama and leave it at that — not as long as its makers insist that it is a documentary, or that it is composed largely of the work of undercover reporters, when at least half of it seems re-enacted. The cause of Burma's democrats is ill-served by hyperbole and the reconstruction of events to fit a version of the truth.

Burma VJ won the top award at the International Documentary Film Festival in Amsterdam in November and was screened at last month's Sundance Festival. It closes with a raid by secret police on DVB's Rangoon secret headquarters — also a reconstruction, although the events it depicts are real and tragic enough. Three reporters were arrested, others went into hiding. Joshua is now in exile, but the authorities know his name — they tortured it out of a friend — and keep his family under surveillance.

Yet I imagine Joshua was comforted by the reaction of Rangoon's police chief. "DVB are the worst," growls Major General Khin Yi in the closing scenes of Burma VJ. "DVB are the ones who broadcast most of the false news about us." My brave Burmese colleagues couldn't ask for a bigger compliment, or for a better reason to continue their extraordinary work.