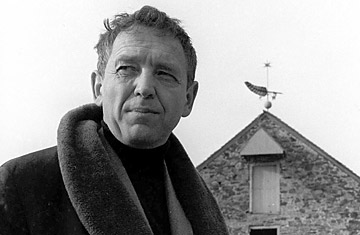

Andrew Wyeth in front of his farm in Chadds Ford, Pa.

The great problem of American art, Andrew Wyeth, died Jan. 16 at 91 at his home in Chadds Ford, Pa. He was a problem first because he so completely refused to be modern in any terms the art world cared about. Long after it was no longer fashionable to practice a flinty, granular realism, Wyeth's brushwork specified the world in almost molecular detail. But even worse was his popularity, which was enormous. Until the other Andy--Warhol--came along, Wyeth and Norman Rockwell were the two most widely recognized names in American art.

Wyeth's skills as a draftsman--and maybe as a showman--are owed to his boisterous, demanding father, the gifted illustrator N.C. Wyeth. Andrew also had a knack for self-promotion that came to a head with the curious case of the so-called Helga pictures--a cache of some 240 "undiscovered" portraits and nudes, featuring his sister's married housekeeper. Insinuations of a secret affair (which the painter later admitted never occurred) put Wyeth on the cover of TIME and his work in the National Gallery of Art.

Still, the quiet spareness of his pictures--and of the people in them, with their Yankee rectitude and their Nordic inwardness--seems to belong to some prelapsarian America, predating automobiles and television.

Wyeth's most famous canvas, Christina's World, hangs in a marginal anteroom in New York City's Museum of Modern Art; Christina, splayed across a field and gazing toward a house on the horizon, could easily be looking at MOMA itself--the citadel she has not entirely entered, even if she is inside. But the canons of art history have loosened in recent decades, enough so that no full picture of the modern era can exclude Wyeth's legacy. Who knows? Someday MOMA may even bring Christina in from the cold.