(2 of 3)

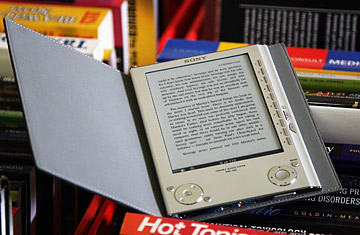

If you think about it, shipping physical books back and forth across the country is starting to seem pretty 20th century. Novels are getting restless, shrugging off their expensive papery husks and transmigrating digitally into other forms. Devices like the Sony Reader and Amazon's Kindle have gained devoted followings. Google has scanned more than 7 million books into its online database; the plan is to scan them all, every single one, within 10 years. Writers podcast their books and post them, chapter by chapter, on blogs. Four of the five best-selling novels in Japan in 2007 belonged to an entirely new literary form called keitai shosetsu: novels written, and read, on cell phones. Compared with the time and cost of replicating a digital file and shipping it around the world--i.e., zero and nothing--printing books on paper feels a little Paleolithic. (See 25 must-have travel gadgets.)

And speaking of advances, books are also leaving behind another kind of paper: money. Those cell-phone novels are generally written by amateurs and posted on free community websites, by the hundreds of thousands, with no expectation of payment. For the first time in modern history, novels are becoming detached from dollars. They're circulating outside the economy that spawned them.

Cell-phone novels haven't caught on in the U.S.--yet--but we have something analogous: fan fiction, fan-written stories based on fictional worlds and characters borrowed from popular culture--Star Trek, Jane Austen, Twilight, you name it. There's a staggering amount of it online, enough to qualify it as a literary form in its own right. Fanfiction.net hosts 386,490 short stories, novels and novellas in its Harry Potter section alone.

No printing and shipping. No advances. Maybe publishing will survive after all! Then again, if you can have publishing without paper and without money, why not publishing without publishers?

Vanity of Vanities, All Is Vanity

When Genova had reached the end of her unsuccessful search, she told the last literary agent who rejected her, "I've had enough of this. I'm going to go self-publish it." "That was by e-mail," she says. "He picked up the phone and called me within five minutes and said, 'Don't do that. You will kill your writing career before it starts.'"

It's true: saying you were a self-published author used to be like saying you were a self-taught brain surgeon. But over the past couple of years, vanity publishing has become practically respectable. As the technical challenges have decreased--you can turn a Word document on your hard drive into a self-published novel on Amazon's Kindle store in about five minutes--so has the stigma. Giga-selling fantasist Christopher Paolini started as a self-published author. After Brunonia Barry self-published her novel The Lace Reader in 2007, William Morrow picked it up and gave her a two-book deal worth $2 million. The fact that William P. Young's The Shack was initially self-published hasn't stopped it from spending 34 weeks on the New York Times best-seller list. (See the top 10 fiction books of 2008.)

Daniel Suarez, a software consultant in Los Angeles, sent his techno-thriller Daemon to 48 literary agents. No go. So he self-published instead. Bit by bit, bloggers got behind Daemon. Eventually Penguin noticed and bought it and a sequel for a sum in the high six figures. "I really see a future in doing that," Suarez says, "where agencies would monitor the performance of self-published books, in a sort of Darwinian selection process, and see what bubbles to the surface. I think of it as crowd-sourcing the manuscript-submission process."

Self-publishing has gone from being the last resort of the desperate and talentless to something more like out-of-town tryouts for theater or the farm system in baseball. It's the last ripple of the Web 2.0 vibe finally washing up on publishing's remote shores. After YouTube and Wikipedia, the idea of user-generated content just isn't that freaky anymore.