Prosperity has its favorite hobbies, its gold-trimmed roadsters and superyachts and the million-dollar platinum fishing lure studded with 100 carats of diamonds. But in an age of austerity, when we seek satisfaction on the cheap, some pursuits are all about value, but not necessarily about money. This is the beauty of the collector's world. When you don't like the look of the economy, you get to make your own.

At the moment, people have decided that anything related to Barack Obama--not just posters and T shirts but magnets and mouse pads and coasters and clocks--has special value. For most people, I don't think it has much to do with investment; it's about placing inspiration under glass. You can capture historic moments in memory, but those fade and fracture. The buttons allow instant replay: the speeches, the spectacle, the grand finale. And who knows: maybe someday they'll have public as well as private value.

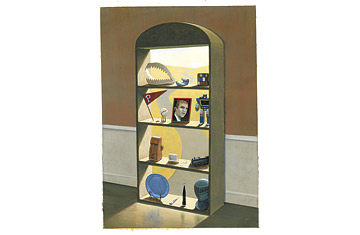

The test of a collector is to acquire the most treasure for the least money. It was during the Depression that my grandfather became a great collector. He was not born rich, but he had a genius for money, especially for primitive and "odd and curious" currencies. In 1934, the New York Times described his coin collection as one of the largest in the world. "A lot of people call us crazy," he told the paper, "but I think it's a worthwhile hobby. It keeps me broke most of the time." Like any master hunter, he had a scavenger's instincts. He would write to missionaries serving in the most remote corners of the world, offering a modest contribution in return for two samples of the local currency. He would sell one and keep the other, a self-financing collection that eventually grew to more than 200,000 pieces--from ancient Etruscan rings and Incan gold to Kenyan elephant tails and Babylonian clay tablets, all of which he kept in a vault in the basement of his house.

I understand the numismatist's desire to possess the objects by which we capture value. (This, of course, is also known as banking.) But the collective unconscious goes further and deeper, and starts long before we know the meaning of a nickel. Children are natural curators, classifying their Barbies or Bakugan, holding on to Happy Meal toys until they have a full set. Freud had a theory about this: not surprisingly, it had to do with toilet training and the trauma of relinquishing a part of oneself. But it's not a need we outgrow. Over the course of his life and travels, Freud acquired more than 2,000 statues, vases and terra-cottas, plus some phalluses, of which his favorites stood in a row on his desk. "I must always have an object to love," he confessed to Carl Jung.

We find ourselves now in a golden age of obsessive acquisition. We watch Antiques Roadshow and mentally inventory the attic, troll the tag sales, join the National Toothpick Holder Collectors Society. Once treasures were prized for their scarcity, but now mass production creates mass disposal and the chance to find worth in the weird and worthless: bottle caps and matchbook covers, swizzle sticks and toilet seats. (There's a toilet-seat-art museum in San Antonio, Texas.) Since objects of desire tend to hold some special meaning, they let people connect with the instant intimacy of shared fixation. If you doubt this, stop by modernmoisttowelette.com to compare notes about the world's best hand wipes and their unexpected uses.