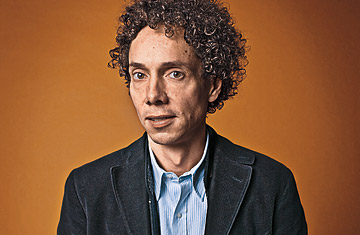

Malcolm Gladwell

He started with the lawyers. "Why do they all have the same biography?" he wondered. "We take it for granted that there's this guy in New York who's the corporate lawyer, right? I just was curious: Why is it all the same guy?" It takes a special kind of brain to be curious about New York City lawyers. Such a brain belongs to Malcolm Gladwell, 45, author of The Tipping Point and Blink, the founding documents of the now best-selling genre of pop economics, which together have sold more than 4.5 million copies.

Slender, with elfin cheekbones and a distinctive bloom of spirally brown hair, Gladwell is one of those clever people who actually looks clever. His curiosity about high-achieving lawyers was the germ of his third book, Outliers, which will be published Nov. 18. It's a book about exceptional people: smart people, rich people, successful people, people who operate at the extreme outer edge of what is statistically possible. Robert Oppenheimer. Bill Gates. The Beatles. And yes, fancy lawyers.

Gladwell's goal is to adjust our understanding of how people like that get to where they are. Instead of the Horatio Alger story of success — a gifted child who through heroic striving within a meritocratic system becomes a successful (rich, famous, fill in your life goal here) adult — Outliers tells a story about the context in which success takes place: family, culture, friendship, childhood, accidents of birth and history and geography. "It's not enough to ask what successful people are like," Gladwell writes. "It is only by asking where they are from that we can unravel the logic behind who succeeds and who doesn't." Outliers is, in its genteel Gladwellian way, a frontal assault on the great American myth of the self-made man. (And they mostly are men. There aren't a lot of women outliers in Outliers.)

In some ways, Gladwell himself is, if not an outlier, then at least an outsider. He is both the son of a Jamaican woman in overwhelmingly white Canada and an academic kid from a working-class town (Elmira, Ont.). But the outsider had an in: his father, a mathematician, brought him into the rarefied world of the university. That context is not unconnected to his later success. "As a kid, 11 or something, we would go to his office, and I would wander round," he says. "I got that sense that everybody was so friendly, and their doors were open. I sort of fell in love with libraries at the same time." Now Gladwell, a New Yorker staff writer, specializes in milling crunchy academic material — psychology experiments, sociological studies, law articles, statistical surveys of plane crashes and classical musicians and hockey players — into prose so silky and accessible, it passes directly into the popular imagination in the form of memes. The most obvious candidate for memification in Outliers is a little gem Gladwell calls the 10,000-Hour Rule. Studies suggest that the key to success in any field has nothing to do with talent. It's simply practice, 10,000 hours of it — 20 hours a week for 10 years.

Outliers is a more personal book than its predecessors are. If you hold it up to the light, at the right angle, you can read it as a coded autobiography: a successful man trying to figure out his own context, how success happened to him and what it means. Gladwell is asking, as he puts it over lunch, "whether successful people deserve the praise we heap on them."