(2 of 4)

This sort of thinking is already familiar to much of corporate America. For globalized companies, risk comes from all directions--contaminated products from China, terrorist attacks on facilities in the Middle East, Katrina- and Ike-size weather events at home--which has led to the rise of what the consultants call enterprise risk management. The level of risk a company is willing to take is articulated by the board of directors, and then measures of risk taken are gathered and fed up to the highest levels of management.

In 2005, when the board of postal-machine maker Pitney Bowes decided to analyze risk more systematically, the company listed 16 categories of risk--from supply chain to reputation--and assigned a senior executive to be in charge of each one in an attempt to drive the new ethos into the corporate culture. What was important was that the firm also made a deliberate decision that risk was not something that could be reduced to a number. "We have a much more holistic discussion about a business and why we have it," says vice president and treasurer Helen Shan. "It becomes strategic, instead of simply, Do we get insurance to cover a potential loss?" In a speech at an industry conference in October, Federal Reserve governor Randall Kroszner urged financial firms to take a similar tack. Weighing risks, as well as potential returns, he said, "should be part of the calculus for all decision-making," and "assessing potential returns without fully assessing the corresponding risks to the organization is incomplete, and potentially hazardous, strategic analysis."

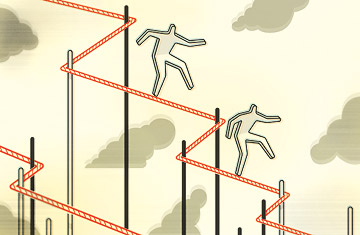

And yet that, by and large, was how the biggest players in the financial-services sector acted in the run-up to the crisis. Taking on risk from instruments like credit-default swaps and collateralized debt obligations (CDOs) was treated as a profit center, often with little oversight of the mathematical models that spit out numbers about what it was all worth. The models proved spectacularly wrong because they precluded the possibility of an outsize event. Once big shocks, like declining home prices, started hitting, the models broke down. According to a report by a group of U.S. and international regulators, while some firms tried to understand what would happen to their models in truly adverse conditions, plenty of others didn't. In some cases, finance outfits barely examined their products, instead relying on the evaluations of outside ratings agencies, even as they accumulated more and more of those assets.

As it became clearer that the U.S. housing market was in an asset bubble, line managers could often see how slapdash the standards being employed were. But with compensation aligned with metrics like revenue and market share, and not risk mitigation, the forward push continued. When managers did articulate problems, they were often ignored. In August 2007, one of Merrill Lynch's top risk managers warned his boss that a decision to wager $3 billion on indexes of mortgage-related securities was too risky. The firm made the bet anyway; three months later, the risk manager left. "The psychology during a boom makes it very difficult to come up with large stress scenarios and get management to consider them to be credible," says Ed Hida, a partner in Deloitte & Touche's risk- and capital-management practice.