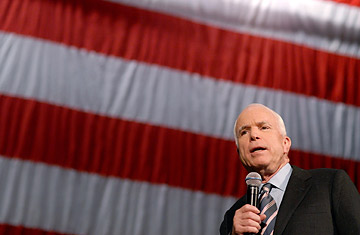

Senator John McCain speaks at a town hall meeting.

"I had the courage and the judgment to say that I would rather lose a political campaign than lose a war," John McCain said during a Rochester, N.H., town meeting on July 22. "It seems to me that Senator Obama would rather lose a war in order to win a political campaign." It was a remarkable statement, as intemperate a personal attack as I've ever heard a major-party candidate make in a presidential campaign, the sort of thing that no potential President of the United States should ever be caught saying. (A prudent candidate has aides sling that sort of mud.) It was also inevitable. You could see McCain's frustration building as Barack Obama traipsed elegantly through the Middle East while the pillars of McCain's bellicose regional policy crumbled in his wake. It wasn't only that the Iraqi government seemed to take Obama's side in the debate over when U.S. forces should leave (sooner rather than later). McCain was being undermined in Washington as well, by his old pal George W. Bush, who seemed to take Obama's side in the debate about whether to talk to Iran. Bush sent a ranking U.S. diplomat to negotiate with the Iranians on nuclear issues--and also let it be known that a U.S. Interests Section could soon be established in Tehran, the first U.S. diplomatic presence on Iranian soil since the 1979 hostage crisis.

In the end, both Obama and McCain seemed to have a piece of the truth about Iraq, but Obama's truth was larger and more strategic. Obama had been right about the war in the first place. It was a disastrous idea, a phenomenal waste of lives and American credibility that diverted focus from our real enemy, al-Qaeda in Afghanistan and Pakistan. And Obama was right about the war now: the progress in Iraq was enabling a quicker withdrawal--a plan already hinted at by Bush. And Obama was right about the future: the Iraqis don't want long-term U.S. bases on their territory, a McCain keystone and the source of his infamous comment about staying in Iraq for 100 years. McCain's piece of the truth was tactical: he was right about the surge and right about the brilliance of David Petraeus' battle plan, which had helped quiet down Iraq. McCain was justifiably infuriated that Obama wouldn't acknowledge that success--indeed, Obama seemed to understand that he was pushing McCain's buttons, hoping perhaps to elicit McCain's Vesuvian temper, and in Rochester the eruption occurred.

McCain's greatest claim to the presidency--his overseas expertise--now seems squandered. He has appeared brittle and inflexible, slow to adapt to changes on the ground, slow to grasp the full implications not only of the improving situation in Iraq but also of the worsening situation in Afghanistan and especially Pakistan. Some will say this behavior raises questions about his age. I'll leave those to gerontologists. A more obvious explanation is that McCain has straitjacketed himself in an ideology focused more on enemies (real and imagined) than on opportunities. "It is impossible to ignore the many striking parallels between [McCain] and the so-called neoconservatives (many of whom are vocal and visible supporters of his candidacy)," writes the Democratic diplomat Richard Holbrooke in a forthcoming issue of Foreign Affairs. "I don't know if John has become a neocon," says a longtime friend of the Senator's, "but he sure has surrounded himself with them."

Neoconservatism in foreign policy is best described as unilateral bellicosity cloaked in the utopian rhetoric of freedom and democracy. McCain hasn't always sided with the neocons--he opposed torture, wants to close down Guantánamo--but his pugnacity seems a natural fit with theirs. He has been militant on Iran, though even there his statements have been tactical rather than strategic: his tactic is not to talk to the bad guys. The strategic question here is whether to go for regime change or diplomatic engagement. McCain hasn't said he was for regime change, but he has rattled sabers noisily, joked about bomb-bomb-bombing Iran and surrounded himself with, and been funded by, Jewish neoconservatives who believe Iran is a threat to Israel's existence. He has also taken a rather exotic line on Russia, which he wants to drum out of the G-8 organization of major industrial powers (a foolish proposal, since none of the other G-8 members would abide by it). His notion of a "League of Democracies" seems a transparent attempt to draw a with-us-or-against-us line in the sand against Russia and China. But that's the point: McCain would place a higher priority on finding new enemies than on cultivating new friends.

The sudden collapse of McCain's Middle East policy is a stunning event, although McCain's regional stridency raised questions from the start. This is a long campaign--with, I fearlessly predict, at least one major Obama downdraft to come--but John McCain seems panicked, and in deep trouble now. time.com/swampland