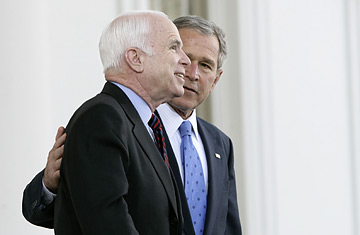

Republican U.S. presidential nominee Senator John McCain is greeted by U.S. President George W Bush at the Rose Garden at the White House on March 5, 2008.

(2 of 3)

During Bush's first eight months in office, virtually every high-profile position McCain took seemed designed to antagonize the new President. "John did what he thought was right," says a close McCain associate. "If it happened to be something that ticked off Bush, so much the better." The antipathy was mutual. According to several veterans of the Bush White House, there was an unofficial policy in effect to block people who had worked on McCain's campaign from getting any of the thousands of jobs the new Administration was doling out.

Daschle and other Democrats involved in the quiet efforts to woo McCain recall that he was willing to listen to their pitch that he quit the GOP in the spring of 2001 and become an independent. Most McCain loyalists insist now that he never seriously considered it. But they do concede that Ted Kennedy discussed the idea with McCain on more than one occasion. Mark Salter, McCain's closest aide, joined the Senator on that first visit to Kennedy's office and waited outside. "Teddy was just talking to me about switching parties," McCain told Salter when it was over. "What'd you tell him?" Salter asked. "No," replied McCain. "But he wants to talk to me again."

In another sign of unhappiness with the Bush regime, McCain's political advisers were exploring whether he could run for President, and win, as a third-party candidate against Bush in 2004. The assumption was that McCain was too old to wait until 2008 (he'll turn 72 in August) and too toxic within the party to run as a Republican again. "Not only was 2008 seen as too late, but we couldn't get our heads around the idea that he would be acceptable [to the GOP]," says one of those advisers. But running as an independent was deemed futile. "We looked at it, and it just wasn't feasible," the adviser says. "Third-party candidates don't win."

After Jeffords left the GOP, throwing the Senate to the Democrats, the White House grew briefly interested in McCain. Out of the blue, John and Cindy were invited to a private dinner in the residence with George and Laura. It lasted all of an hour. When Congress passed the McCain-Feingold campaign-finance-reform bill in early 2002, the legislation and its chief sponsor were so popular that Bush chose to swallow hard and sign it. According to a former White House official who was involved in the discussion, the President rejected the idea of holding a public signing ceremony. "He didn't want to give McCain the satisfaction," says the former official. McCain was informed in a telephone call from a midlevel White House aide that the bill had finally become law.

Despite his public support for Bush after 9/11, McCain had deep misgivings about him as Commander in Chief. In March 2002, he and two other Senators were at the White House, briefing Condoleezza Rice, the National Security Adviser, about their recent meetings with European allies when Bush unexpectedly stuck his head in the door. "Are you all talking about Iraq?" the President asked, his voice tinged with schoolyard bravado. Before McCain and the others in the room could do more than nod, Bush waved his hand dismissively. "F___ Saddam," he said. "We're taking him out." And then he left.

McCain was appalled. He was a Republican, and a hawk, and exactly one year later he would enthusiastically support the decision to topple the Iraqi regime by force. But to McCain, his encounter with Bush that day was more evidence of the shallow intellect and dangerous self-regard possessed by the man to whom he had lost an acrimonious contest two years earlier. Later, McCain would retell the story and shake his head incredulously. "Can you believe this guy?" he asked. "He's the President!" He didn't say it, but the continuation of the thought hung in the air: Can you believe this guy is President--instead of me?

An Uneasy Truce

In the spring of 2004, John Kerry secretly urged his fellow Vietnam vet to join him on a unity ticket. It was, to put it mildly, a full-court press: Kerry offered to make McCain both Vice President and Secretary of Defense and to give him control of foreign policy. Kerry lobbied McCain's wife Cindy and even enlisted the help of Warren Beatty, with whom McCain had become friendly. McCain turned Kerry down. Aides say he sincerely believed that Bush had been and would be a better President than Kerry.

By then it was dawning on McCain's circle of advisers that with no Vice President or other heir apparent to Bush in the mix, their man could run again in 2008--but he'd have to improve his standing within the GOP. In May 2004, without telling McCain, John Weaver asked Mark McKinnon, Bush's ad man, to set up a meeting between him and Karl Rove. Onetime allies in Texas, Weaver and Rove had been feuding since 1988. "This was historic. This was like the Hatfields sitting down with the McCoys," says McKinnon. Rove agreed to the meeting but wanted McKinnon there as a witness. At a Caribou coffee shop not far from the White House, McKinnon observed as Weaver and Rove buried the hatchet. Weaver suggested McCain was willing to campaign for the President's re-election. Rove seemed surprised. "We didn't know he would help," Rove said. "Nobody asked," replied Weaver.

It wasn't long before McCain was embracing Bush--literally. A photo of him awkwardly hugging the President has become the iconic image of their rapprochement, one that Democrats are already using against him. McCain, at least, took the embrace to heart: nobody campaigned harder for Bush's re-election than he did. The very fact that he'd fought so many times with the President only enhanced the value of his endorsement. "[McCain] was our most important surrogate," says Terry Nelson, who was political director of Bush's re-election campaign and, for a time, campaign manager for McCain's 2008 bid. But the two men remained situational allies, not friends. In the minutes before Bush's final debate with Kerry, McCain was full of kinetic energy as he delivered a pep talk to the President in a holding room. "This is the most important moment of your life!" he barked at Bush. "You're gonna be great!" Later, Bush told aides that he found McCain's intensity off-putting. "McCain was wound up tight all the time on the campaign trail," says a Bush aide. "That's just not how the President is. He thought it was over the top."

Balancing Act