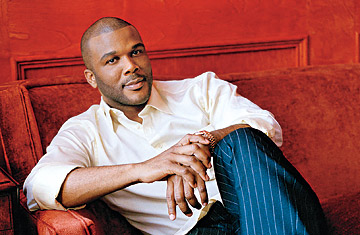

Tyler Perry

(2 of 2)

Actually, blend is the wrong word. Perry's shows are contradictorily and simultaneously rude, forgiving, uplifting, demeaning. Comedy will get churning wildly, then stop in its tracks for a confession of spousal or child abuse. Laugh-cry, empathize-criticize: the mood changes so rapidly in these anachronistic exhibitions that they can seem defiantly postmodern.

For shows that attract a church crowd, Perry's are on the gamy side. Most of the women wear low-cut, skintight frocks. The young men tend to be extravagantly muscular; they frequently take their shirts off, to the oohs of the audience.

Usually, the supporting players carry the melodrama, and Perry's Madea shoulders the comedy. Black actors playing fat women is not exactly an innovation, as Martin Lawrence and Eddie Murphy can attest. But the 6-ft. 5-in. (1.96 m) Perry, who in civvies has the smooth good looks of a Will Smith, cuts an arresting figure. Outfitted in a purple print dress, giant glasses and sandbag bosom, carrying a purse with three handguns and punctuating every comment with the wave of a cigarette, the star stomps around the stage shouting out orders and ridiculing the supporting characters for being too short, too fat or insufficiently black. In these "recorded live" stage performances, he also evidently enjoys breaking the other actors' rhythm. You're encouraged to believe that this is a free-form stage dress rehearsal and that Perry takes the director's prerogative to step out of character and boss his cast around.

Madea may be God-fearing, but she has the mouth of a black Don Rickles. Fingering her daughter's filmy nightgown in Madea's Family Reunion, she says, "That's them twins Polly and Esther; that ain't no silk." Her remorseful granddaughter "ain't apologizing, she's apolo-lyin'." And if the insults don't hit the mark, she can always use the pistols in her purse. "I got more weapons in here than the U.S. dropped on the Taliban," she shouts. "You don't wanna mess with me."

Ms. Mabel is more than the comic relief in these plays. She's the moral arbiter, the fearless truth teller, the preacher of racial pride. In Diary, her well-bred daughter is about to confront the hussy who stole her man. Madea butts in, "No, you're gonna deal with her like a white woman. I'm gonna deal with her like a black woman."

Does Perry's flaunting of African-American stereotypes amount to blackface? There's no question that among the weeping queens, strutting kings and ego-deflating jokers in his pack, he does play the race card. But he's dealing it to fellow blacks, and if enough of them didn't love it, he couldn't have afforded the lavish new house he built in suburban Atlanta. You could also ask if Perry is mocking the folks he hopes to uplift. But his form of comic melodrama depends on creating emotional extremes, acute cartoons of recognizable behavior, people who hurt and get hurt. Public humiliation is the penance his stage characters must endure before they are absolved in a final embrace and bring the curtain down with a full-throated gospel song.

It would be nice if some of the down-home fervor and neck-snapping incongruities of his stage shows could be duplicated in movies. They might not cross over to the wider audience, but that shouldn't concern Perry. His core crowd loves him. And, he surely believes, so does Jesus.