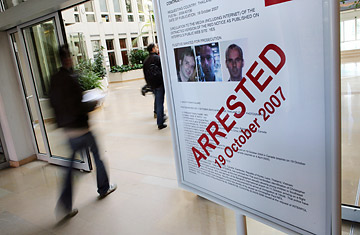

The entrance to the Interpol headquarters in Lyon, France.

(2 of 2)

Inside the Nerve Center

Despite such successes, the data has serious limitations, which become evident the moment one steps into Interpol's command center. One morning in January, Javier Sánchez, an Interpol operational assistant from Barcelona, sat hunched over a computer in the Lyons office, attempting to find a man who had traveled across three continents on stolen documents, and then vanished in São Paolo. Two days earlier, Mexican officials had spotted his stolen Portuguese passport on Interpol's list when he flew into Mexico City from Frankfurt. They deported him back to Germany, where he presented a second stolen passport, this one Brazilian; German officials then deported him to São Paolo, where he disappeared. Interpol's databases had worked well — but not fast enough to outwit him. Nor did they offer any clues as to whether he was a threat or harmless. "He could be nothing," says Sánchez, who had spent two days alerting officials in several countries about the passenger. "Or he could be a fugitive, or a terrorist."

That uncertainty as to whom Interpol is tracking has roused strong unease among civil-rights groups. They point out that, unlike law-enforcement services such as Scotland Yard or the FBI, Interpol does not report to any government. "There is a principle of openness and accountability at stake here which is extremely vital," says Simon Davies, director of Privacy International, a London-based advocacy group that tracks surveillance of civilians. Davies worries that the data collected from countries is sometimes faulty, potentially targeting innocent people. "At least on the national level there is some accountability," he says. "But in Interpol, the technology and techniques aren't subjected to the same kind of scrutiny or oversight."

Interpol officials say they encourage countries to send detailed data about wanted citizens in order to avoid such mistakes, and they stress that its constitutional rules allow for strict independent oversight of its activities and finances. Yet Western governments — typically with plenty of money to invest in their own national police and intelligence services — often prefer to keep tight control of their data rather than share it with Interpol, not least because its members include countries with which they have tense relationships, such as Cuba and Syria. "The irony is that countries which Interpol would like to cooperate most with are the least likely to cooperate," says Deflem. Aside from such political tensions among members, Interpol also has to keep an eye on its members' integrity. In December, Interpol's president, Jackie Selebi, who was also South Africa's police commissioner, was indicted for corruption in South Africa and forced to resign both positions.

More than six years after 9/11, Noble says there is still a "gaping hole" in the world's security — passengers aren't screened before they board international flights. E.U. officials have already said that people who book air tickets to Europe will in future need to supply personal details to airlines, which will in turn pass them to European security services — though they have not specified that they will check the details against Interpol's lists. U.S. consulates are aiming to check all travelers applying for visas against Interpol lists, says Washington director Renkiewicz. While Davies says those new rules will "add to the risk of failure," Noble argues that it may be worth the occasional mistake if the payoff is averting his nightmare scenario of a passenger carrying a nuclear device or biological weapon onto a plane. If that were to happen, he says, "people will never forgive us." As a personal reminder of what's at stake, Noble has hung in his office two photographs of the Manhattan skyline that were taken before the World Trade Center was destroyed. "It shows us what's possible," he says. "After all, we never thought 9/11 was possible."

If there is another major attack, Noble hopes that someone other than his brother will alert him. This time, he would expect Interpol to be a key player, ready at last to shed its image as an afterthought in the world of law enforcement.