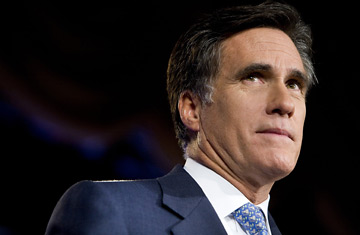

Mitt Romney.

(2 of 2)

Someone else took notice as well. No one has fought longer and harder for universal health coverage than Senator Edward Kennedy; he introduced a national health-insurance bill back in 1970. But he and the Governor were not exactly allies. Romney had challenged Kennedy for his Senate seat in 1994 in a nasty race. Reading the first outlines of Romney's plan in the Boston Globe, Kennedy decided the Republican Governor was serious about the issue, and he told his staff to reach out to Romney's advisers. Before long, Romney was in Kennedy's office in Washington, taking his PowerPoint slides with him. "Had Senator Kennedy said, 'This is a lousy idea, and I don't want anything to do with it,' I would have been back at square one," he admits.

Kennedy was sold, and both men turned to the question of how to pay for the plan. Part of the money could be shifted from the existing $1.1 billion fund through which hospitals had been compensated for the care they were providing the uninsured. But to fund universal coverage, they desperately needed to persuade HHS Secretary Tommy Thompson to allow Massachusetts to keep the $385 million in Medicaid funds that Washington was threatening to take away. The money would also give them leverage back home with health-care providers and businesses, two powerful constituencies and potential opponents of reform.

Their talks with Thompson went right down to the wire. The HHS Secretary signed the deal in a marathon negotiation with Romney and Kennedy that ended on Jan. 26, 2005, his last day on the job, while his going-away party was getting under way. The agreement stipulated that the commonwealth could keep the money but only if it passed a universal-coverage law.

That outcome was far from certain. Romney and his PowerPoint traveled from one end of Massachusetts to the other. But as a Republican, Romney had very little leverage with the legislature, where the GOP's representation was so small it was less a minority than a cult. What's more, the senate and the house had very different ideas of what they wanted to do. As the two chambers squabbled, the Medicaid money was in danger of slipping away.

On a Sunday morning in February 2006, Romney personally taped handwritten notes to the doors of senate president Robert Travaglini and house speaker Salvatore DiMasi, begging them not to let this opportunity die. The speaker, for one, wasn't impressed. "A cheap publicity stunt," DiMasi says. Recognizing the limits of his own influence, Romney turned to Kennedy once again. "I asked for his help on certain legislators: 'Could you give a call on this one?'" Romney says. On March 22, 2006, Kennedy did more than that. He went to the floor of both the house and the senate on Beacon Hill and spoke in very personal terms about the battles with cancer his son and daughter had faced. "This whole issue in terms of universal and comprehensive care has always burned in my soul," Kennedy said. The Federal Government had failed the country on health care, he told the politicians , but "Massachusetts has a chance to do something about it."

The bill that emerged from the legislature two weeks later was different in many respects from what Romney had initially proposed. It increased reimbursement for hospitals, which Romney liked, but added more people to the Medicaid rolls, which he didn't. There were far too many requirements placed on insurance companies for Romney's tastes, and he used his line-item veto on the bill's stipulation that employers who don't cover their workers pay $295 per employee each year into a fund to subsidize coverage. The lawmakers easily overrode it, as Romney surely knew they would. "He was trying to protect his own political position for the future, as opposed to creating a substantive policy," DiMasi says, still irked by what he considers Romney's grandstand play to the GOP base. "He knew full well he was running for President of the United States."

Everyone around Romney had assumed this achievement would be a centerpiece of his presidential campaign, showcasing the data-driven, goal-oriented, utterly pragmatic side of Romney. But that side of him has emerged only rarely on the 2008 trail. Instead, he rarely discusses the details of his Massachusetts plan and certainly doesn't tout his partnership with Kennedy. As a presidential candidate, he cautiously adheres to by-the-book Republican dogma of giving individual states leeway in the form of tax breaks to design their own reforms.

Romney explains this seemingly odd tactical choice by arguing that he never intended for his Massachusetts plan to be a role model for the rest of the country. "An individual mandate in most states today--in all states but one--would be irresponsible and unfair," Romney says. "Because in most states today, insurance is too expensive." It does seem fair, however, to wonder: What happened to that other Mitt Romney, the one who wouldn't be satisfied until he found the answer himself?