Sept. 11 delivered both a shock and a surprise--the attack, and our response to it--and we can argue forever over which mattered more. There has been so much talk of the goodness that erupted that day that we forget how unprepared we were for it. We did not expect much from a generation that had spent its middle age examining all the ways it failed to measure up to the one that had come before--all fat, no muscle, less a beacon to the world than a bully, drunk on blessings taken for granted.

It was tempting to say that Sept. 11 changed all that, just as it is tempting to say that every hero needs a villain, and goodness needs evil as its grinding stone. But try looking a widow in the eye and talking about all the good that has come of this. It may not be a coincidence, but neither is it a partnership: good does not need evil, we owe no debt to demons, and the attack did not make us better. It was an occasion to discover what we already were. "Maybe the purpose of all this," New York City Mayor Rudy Giuliani said at a funeral for a friend, "is to find out if America today is as strong as when we fought for our independence or when we fought for ourselves as a Union to end slavery or as strong as our fathers and grandfathers who fought to rid the world of Nazism and communism." The terrorists, he argues, were counting on our cowardice. They've learned a lot about us since then. And so have we.

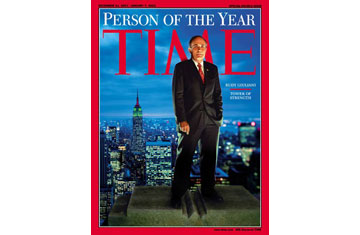

For leading that lesson, for having more faith in us than we had in ourselves, for being brave when required and rude where appropriate and tender without being trite, for not sleeping and not quitting and not shrinking from the pain all around him, Rudy Giuliani, Mayor of the World, is TIME's 2001 Person of the Year.

If the graves alone were the measure, Osama bin Laden would own this year; we lost more lives on Sept. 11 than in any terrorist attack in U.S. history. And bin Laden did more than kill people. We had just packed up and stored away the century of Hitler and Stalin--both Men of the Year in their time--which we imagined had shown us the depths to which a despot could sink. To watch bin Laden sit in delight and create a skyscraper with his hand--like a child playing Here's the Church, Here's the Steeple--then slowly crumple it into a fist was to confront not only the nature of evil but how much we still don't know about it.

But bin Laden is too small a man to get the credit for all that has happened in America in the autumn of 2001. Imagination makes him larger than he is in order that he fit his crime; yet those who have studied his work do not elevate him to the company of history's monsters, despite the monstrousness of what he has done. It is easy to turn grievance into violence; that takes no genius, just a lack of scruple and a loaded gun. The killers he dispatched were braver men than he; he has a lot of money and a lot of hate, and when he is gone there will be others to take his place.