The Rise of Moderate Islam

As we wait for the Salafi leader Kamal Habib at the Cairo Journalists' Union, a sudden panic comes over me. I've just noticed that my translator, Shahira Amin, an Egyptian journalist, is wearing a sleeveless top and that her hair is uncovered. In my experience, Salafis, adherents of a very strict school of Islam, take a dim view of such displays of femininity. I recall a time in Baghdad when a Salafi preacher cursed me for bringing a female photographer to our interview, and an occasion in the Jordanian city of Salt when another Salafi leaped from his chair and thwacked his teenage daughter on the arm when she accidentally entered the room without covering her face from my infidel eyes.

I've heard reports that Habib is not the hard-liner he was in the 1970s, when he co-founded the radical Egyptian Islamic Jihad, or the 1980s, when he was jailed in connection with the assassination of President Anwar Sadat. He gave up politics after a decade in prison, but in the aftermath of the Arab Spring, he has reinvented himself as a leader of a more moderate party. He has held press conferences at the union, so presumably he's had to make his peace with women who don't cover their hair. But I fear he may draw the line at a sleeveless top.

I needn't have worried. When Habib arrives, he shouts a jolly greeting from across the room and then bounds over. He's wearing a blue blazer and clutching a smart phone. He looks my translator straight in the eye and extends his hand to shake. They exchange complaints about the beastly humidity. Would Shahira like a Pepsi? he asks solicitously.

Only weeks before my arrival in Cairo, Salafis had burned down Coptic Christian churches in the Imbaba neighborhood, perhaps 15 minutes from where we're sitting. Salafi men had menaced women who strayed into their neighborhood without adequate covering. Long hounded by the police and secret service of the dictator Hosni Mubarak, the Salafis seemed to be celebrating their newfound freedom with an orgy of violence.

Only weeks before my arrival in Cairo, Salafis had burned down Coptic Christian churches in the Imbaba neighborhood, perhaps 15 minutes from where we're sitting. Salafi men had menaced women who strayed into their neighborhood without adequate covering. Long hounded by the police and secret service of the dictator Hosni Mubarak, the Salafis seemed to be celebrating their newfound freedom with an orgy of violence.

But a few weeks are an eternity in post-Mubarak Egypt. Several Salafi leaders have decided to join the political fray, and they can't afford to let a few thugs make them all look bad. So Habib has decided to organize a big reconciliation meeting with Coptic leaders, and he wants me to know he has no truck with the reactionaries who burned churches. "Khalas. Finished," he says, spreading his hands in a gesture of finality. "The past is the past, and the people who did this terrible thing are from the past. Their time is over."

I had to wonder if Habib's message was custom-made for a Western journalist or whether it offered a glimpse of a new possibility. Over the next few days, in the incipient Arab democracies of Egypt and Tunisia, I find that Islamists of all stripes — from extremist Salafis to members of more orthodox groups like the Muslim Brotherhood — say they are breaking with the past and reinventing themselves as the moderate mainstream. "We can no longer be the party that says 'Down with this' and 'Down with that,'" says Essam el-Erian, a top Brotherhood leader. "The thing we stood against is gone, so now we have to re-examine what we stand for."

As the Arab Spring turns to blazing summer, Islamist movements have quickly formed political parties and mobilized national campaigns designed to unveil their new image before elections in the fall and winter. Paranoid rhetoric about threats to Muslim identity have given way to political messaging that could have been lifted from the party platforms of any Western democracy: It's all about jobs, investments, inclusiveness. A new broom to sweep clean decades of corruption. A new dawn of can-do Islamism.

It's not easy to tell how this is playing outside the political parlors. Many Egyptians, especially the young, are not thinking about their next government; they're still focused on the one they've got. Activists continue to organize weekly demonstrations in Tahrir Square, pressuring the military-led transitional authority to prosecute Mubarak-era crimes. "They're permanently in revolution mode," says liberal politician Hisham Kassem. "They're just not organized for politics."

Organization, by contrast, has always been the Muslim Brotherhood's strong suit. Founded in 1928 to promote Islamic law and values, it has endured brutal suppression by a succession of Egyptian leaders. Estimates of its membership vary from 100,000 to many times that number. In the Mubarak years, open association with the Brotherhood was an invitation to police harassment or worse. The group has long been feared in the West as the source and exporter of radical Islamist ideology: violent groups like Hamas are direct offshoots of the Brotherhood. Some scholars trace the origins of terrorist groups like al-Qaeda to the Islamists. In Egypt, however, the group long ago rejected the rhetoric of violent jihad, and it is seen as a social movement as much as a political entity. Egypt's poor have long associated the Brotherhood with its social services, like free clinics and schools.

Now the Brotherhood needs to broaden its base to include middle-class and affluent Egyptians. Many of the young men and women hanging out on the October 6 Bridge on a Thursday evening — enjoying a cool breeze off the Nile and the chance for some mild flirting — seem comfortable with the idea of an Islamist-led government. "We know these guys. We go to school with them, eat with them, play soccer with them," says Fadel, a 20-year-old university student. "If they come to power, we'll judge them by their results, not the size of their beards."

Under the circumstances, you might expect the Islamists to be reveling in their ascendancy, seeing it as an endorsement of their extreme views. They're doing no such thing. Instead they are herding toward the political center, adopting positions that would be entirely familiar in Western democracies. Leaders of Egypt's Muslim Brotherhood and Tunisia's Ennahda (Renaissance) talk about economic priorities: creating jobs, reducing debt, attracting foreign investment, halting the exodus of skilled labor. There's little talk of Shari'a or of restricting the rights of women or non-Muslim minorities.

To reassure critics who fear that the Islamists will seek to remake Egypt as a theocratic state, the Brotherhood is entering the ring with one hand tied voluntarily behind its back: its new political arm, the Freedom and Justice Party, will contest only half the seats in the first post-Mubarak general elections, expected in the late fall, and will not field a candidate for the presidential election in early 2012. (When a Brotherhood stalwart, Abdel Moneim Abou el-Fatouh, declared his candidacy in May, he was expelled.) This guarantees that the party will not have anything like a majority in the new parliament, which will take on the highly sensitive task of rewriting the constitution. All parties, says el-Erian, will have a say in framing new laws. Why is the Brotherhood giving up a shot at political dominance? El-Erian says it's because "we recognize that it would create fear, and the absence of fear is good for us as much as it is good for Egypt."

The liberals I meet aren't buying this. Some tell me it's an empty gesture: the Brotherhood knows it can't win a majority anyway. Alaa al Aswany, Cairo's most famous living novelist and a prominent liberal, claims that the Brotherhood doesn't have broad support, pointing to recent wins by liberal candidates in bellwether student-union elections at several universities. But he is nonetheless apprehensive. For all its vaunted political principles, al Aswany says, "in the Brotherhood, anything is allowed [in the pursuit of] power, so we can never trust them." Others smell a ruse: the Brotherhood will simply have proxies contest the rest of the seats as independents and will try to win a majority, allowing it to drown out liberal voices in parliament.

It doesn't help that liberal groups are in disarray. The kids who brought down dictators in Egypt and Tunisia have shown little interest in forming political parties. Wael Ghonim, the young Google executive who became the most recognized face of the Tahrir Square revolution, has dropped out of sight. Older liberal pols, who lack the revolutionary credentials of the youth and the organizational skill of the Islamists, are struggling to keep up. Mohamed ElBaradei, the former U.N. nuclear watchdog and Nobel Peace laureate, can't seem to make up his mind whether to run for President.

The liberals are also showing themselves to be poor democrats. Several prominent liberals — ElBaradei among them — have launched a signature campaign to force postponement of the parliamentary elections and get an unelected panel of experts to first remake the constitution. The Constitution First campaign, a Western diplomat in Cairo tells me, "reflects the liberals' uncertainty about how they will do in elections and a desire to lock in some protections." Politically, too, the liberals' call for postponement is nakedly self-serving: it would give them time to try and match the Brotherhood's grass-roots organization.

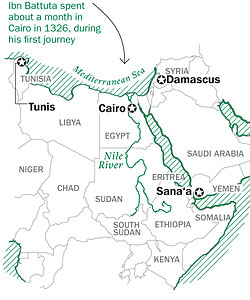

Can the liberals and the Islamists learn to play fairly with each other? The question is being asked not just in Cairo and Tunis but also in Damascus and Sana'a: if religious and secular groups can work together in Egypt and Tunisia, that would send a powerful message to Syria, Yemen and other Arab countries where revolutionary winds are blowing. Western governments, too, have a stake in the answer. Since the fall of Mubarak, much of the discussion in the U.S. and Europe has been about whether his successors can come to terms with the West and maintain peace with Israel. But the first and most important test of the new Arab democracy may be whether its conflicting political tendencies can accommodate each other.

Thus far, the Islamists have shown the greater willingness to deal, and the Obama Administration seems to think they can be expected to behave rationally, not like reactionaries or radicals. U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton confirmed reports in late June that the Administration will upgrade its interaction with the Brotherhood from indirect communication — through Egyptian parliamentarians connected to the Islamists — to direct contact. But the Islamists' conciliatory gestures are not really directed at a Western audience. It's their own countrymen, Egyptians and Tunisians, they want to reassure. (It's remarkable how rarely the U.S. or Israel comes up in my conversations.) The Islamists may have recognized that their radical tune is played out. They've seen in Iran and Gaza the crippling consequences of extremist behavior: Western aid and foreign investment would dry up and possibly be replaced by economic sanctions. As much as they desire power, the Islamists don't want to inherit bankrupt states.

It's also conceivable that they are playing for time to consolidate their position, although there are other plausible explanations. One is that the Arab revolution unshackled the moderate majority within Islamist groups. During the decades of oppressive rule, only the extremists dared speak out, allowing the rest of the world to believe they spoke for the entire movement. With their oppressors gone, moderate Islamists are now in the ascendancy within the Brotherhood. They vastly outnumber the extremists, and in the emerging democracy, this gives them power. They are setting the agenda.

Then there's the sobering prospect of having to run a government, perhaps as the dominant partner in a coalition. El-Erian looks positively gloomy as he ponders the challenges that await. "Jobs, where will they come from?" he says. "We need to create jobs. We need investments, not loans. We need businesses. We need to export more. If we work very hard, in five years Egypt will be a great market." In other words, this is no time to debate the finer points of Koranic jurisprudence.

There is yet one other factor influencing the Islamists to redefine themselves: the powerful political gravity of Tahrir Square. Islamists recognize that the revolution that liberated them was led by an iPad generation with universal, not religious, demands: jobs, justice, dignity. "The young people have told us all what they want, and our agenda should be close to theirs," says el-Erian.

As the Islamists stampede to the political center, there's still room for the outlier, the unreconstructed Salafi. I arrange to meet Abdelmajid Habibi at a café in Tunis. He's a leader of Hizb ut-Tahrir, an extremist group that has not yet been given license to operate as a political party. By coincidence, my Tunisian translator, Salma Mahfoudh, is also a woman; she is dressed in jeans and has her hair uncovered. Habibi is uncomfortable in her presence and keeps his eyes on me even as she speaks with him. It doesn't matter very much if he can't form a political party, he says, because he's not sure he approves of an election or a constitution. "Why do we need a constitution? We already have the Koran, which has all the laws we need as a society." He doesn't believe in modern borders or nations either: the entire Islamic world should submit to a single enlightened ruler.

This is the Salafi worldview I've encountered for nearly 15 years. But wait. As we talk some more, Habibi's line softens. "We think people can only be happy if they follow the Koran," he says. "But if they don't want it, we shouldn't force it on them." As he rises to say goodbye, he smiles at us both. He shakes my hand. And then Salma's.