In Pursuit of Romance

It's 10 minutes to midnight on a Thursday in Riyadh, the start of the Saudi weekend, and even though it's the middle of finals, Tahlia Street swarms with kids in Porsches and Ferraris looking for a good time. Throbbing bass beats back the syncopated rhythm of bleating car horns. The aim is not so much to get through the traffic as to draw attention to the young men in the driver's seats. They lounge in their leather thrones, AC on high and a forearm draped nonchalantly over a rolled-down window, luxury watch on display. Both peacocks and hunters, they have relaxed postures that belie eyes on alert for signs of prey in the passing cars: a foreign driver alone up front, and in the backseat, partially obscured by tinted windows rolled up tight, a woman's vague form.

I survey the scene from the backseat of my friend's SUV, confident in the relative anonymity of her darkened windows. The urgent honking of a nearby car breaks my reverie. A gleaming white Chrysler pulls up alongside. Inside, a young man, the starched and folded peaks of his red-and-white-checked headscarf pulled low in the Stetson-like style popular with hipsters, is waving for my attention. He swerves erratically as he attempts to steer with his knees, giving me a double thumbs-up and a broad grin. Then he raises a laminated placard stenciled with a phone number. After a few seconds, enough time for me to jot down the digits, he shouts across the lane, "Khalas? You got it?" As if to seal the deal, he licks his lips lasciviously, kisses his index finger with an exaggerated pout and blows it like Marilyn Monroe in my direction, then roars off. Welcome to the pickup, Saudi-style.

Salman must have been disappointed to get a phone call from an American journalist. When we meet at a popular café a few days later, he confesses that he received at least 10 calls that night and wasn't entirely sure which car had been mine. Ever the player, he tries to convince me that he "numbered" me, in local parlance, because I was "so beautiful." When I point out that a grandmother could have been behind that tinted window, he shrugs. "How else can I meet girls?"

Over virgin mojitos, Salman describes to me a dating scene like no other. There are no movie theaters in Saudi Arabia, and no bars. Weddings are segregated, as are schools. In Saudi Arabia, where culture and religion conspire to prevent all unregulated contact between men and women, young singles resort to extreme methods in pursuit of romance.

Over virgin mojitos, Salman describes to me a dating scene like no other. There are no movie theaters in Saudi Arabia, and no bars. Weddings are segregated, as are schools. In Saudi Arabia, where culture and religion conspire to prevent all unregulated contact between men and women, young singles resort to extreme methods in pursuit of romance.

In Riyadh, says Salman, numbering can be competitive. Preening males sometimes rent fancy cars in hopes of increasing their chances. "Girls don't give a damn if the boy is good-looking or nice," he complains. "They only care if he is rich." In the five years Salman has been numbering, he has managed to go on several dates and even had a girlfriend for a short while. But at 24, he's looking for something more serious. "Definitely romance," he says. "If I can find a nice, respectable girl this way, I wouldn't mind getting married."

Worlds Apart

"(I can't get no) satisfaction" was certainly not on the sound track to the Arab revolts. But it might very well have been their subtext, according to the well-known Middle East scholar Bernard Lewis, who argued in an interview with the Jerusalem Post that the uprisings were fueled in part by sexual frustration. "In the Muslim world, casual sex, Western-style, doesn't exist," Lewis said. "If a young man wants sex, there are only two possibilities — marriage and the brothel. You have these vast numbers of young men growing up without the money either for the brothel or the bride-price, with raging sexual desire. On the one hand, it can lead to the suicide bomber. On the other hand, sheer frustration."

The theory has drawn virulent rebuttals from some and slow nods of acceptance from others. Some, like Egyptian sexologist Heba Qotb, say the idea that men can't afford to get married is nonsense. Just look at the rate of early marriage in lower-class communities compared with that of the rich. "Late marriages," Qotb says, "are by choice." But Mahmood Takey, a 19-year-old Egyptian university student, says that without a job, he would hardly be considered a good catch. "A guy might have to wait until he is 30 before he gets a job, so of course he is frustrated. We were protesting because of corruption, injustice and unemployment, but absolutely sexual frustration was a part of it." Some men, he says, go to prostitutes, but not if they are religious.

Of course, a 19-year-old might be more concerned about sex than, say, marriage. (Ibn Battuta was obsessed with both: he possessed a strong libido and married numerous times during his travels.) But the reality for many in the Middle East is that marriage isn't just about religiously sanctioned sex. It's about finding a place in society. Prostitutes and Internet porn help assuage some frustrations, even as they introduce guilt and shame, says Qotb, but they can't provide intimacy and social maturity. While most marriages are still arranged, single Saudis are increasingly captivated by Hollywood-style romances beamed in via satellite and the Internet.

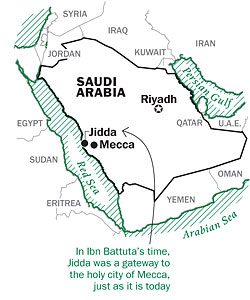

As they attempt to navigate between tradition and modern love, they stumble over the obstacles of Saudi culture, resulting in a unique form of dating that is both an earnest search for connection and fraught with danger. Segregation of the sexes has its origins in both Islam and the early traditions of the peninsula's Bedouin tribes, in which hiding women from the public eye was considered a point of honor — and, in an era predating genetic testing, a way of ensuring that offspring were legitimate. This Bedouin culture has spread across the peninsula, though it is weaker in the Red Sea city of Jidda, where over centuries, pilgrims on their way to nearby Mecca have left a more liberal and cosmopolitan imprint. Men and women had always prayed together in Mecca, but conservative clerics argue that stringent laws originally concerning the Prophet Muhammad's wives should apply to all women.

Others justify the ban on mixing by pointing to social problems elsewhere. "These rules help society avoid the mess you see in the West: illegitimate children, single mothers, abortions and children in orphanages," says Sheik Abdallah al-Oweardi, a self-described moderate religious scholar, citing a recent statistic that 40% of all pregnancies in the U.S. are out of wedlock. The laws against mixing mean that single men and women rarely have an opportunity to meet. Most workplaces are segregated as well, except in medicine, where separation could affect the quality of care. That's one of the reasons, say several young female medical students out celebrating the end of finals, that they chose the profession. "Just like in America, the best place to meet someone is at work," one told me. "And for us, that means the hospital." She asked me not to use her name, mortified that she might be perceived as loose for admitting she was interested in meeting men. (Dating in Saudi Arabia is such a sensitive topic that most people I met spoke on the condition that I use their first name only or no name at all.)

Girls Just Want to Have Fun

Saudi girls go out on the prowl just like boys, ducking even stricter rules. And when they do, they have to make sure they dress the part. Women in Saudi Arabia are required to wear a headscarf and an abaya, a loose, full-length gown. In Riyadh, black predominates. But what looks like a uniform from a distance can be at close range a daring code of communication — a flash of color on the sleeves, enough Swarovski crystals to complete a chandelier. "Of course boys pay attention to our abayas," says Maha, 22. Hers features artfully slashed sleeves that reveal a white satin lining. It's a Friday evening at the mall, and she is fully made up, complete with false eyelashes. "All the girls want to look good. We do our makeup and hair before coming out," she says. And it works. She met her boyfriend at the mall when he walked up to her and offered his number. He didn't have a good line, but he was handsome, she says. Still, the international rules of flirting applied: "I called after a week, so he wouldn't think I was easy."

For two months, their "dates" were limited to two-hour-long phone calls nearly every night. Now she sometimes goes to his house for dinner, chaperoned by his mother or older sister. Occasionally, they hold hands or sneak a chaste kiss if no one is looking. But it never goes further than that. She French-kissed a boy once, she admits, but would never do so with her current boyfriend. "That wouldn't be proper," she says. "He is the man I want to marry."

Once a couple gets past the numbering stage and the phone calls, finding places to go is challenging. Unmarried couples are not allowed to be together in public; if caught, they can be fined or thrown in jail. For a woman, it can mean a humiliating call to her father and a stain on her reputation. Fear of being busted can turn an otherwise pleasant outing into a stressful evening. A mention of the mutaween, or religious police, invokes shudders. "Oh, don't say their name," one woman tells me, looking around nervously. "It will make them come." Just a few weeks before, she and her boyfriend cowered behind a partition for what seemed like hours as the mutaween swept through a restaurant popular with young couples.

Yousuf, a suave bioengineering student with several years of successful pickups, recommends taking dates out to breakfast, when the "bearded ones," as he calls them, are less likely to be prowling around. Another trick, he says, is to go to a mall or hotel owned by one of the prominent princes who have a tacit agreement with the mutaween that they don't go to his properties. Yousuf's favorite place is the top of Riyadh's ritzy Kingdom Tower, where a sky bridge provides a breathtaking view of the city — along with an added perk. "If you are lucky, she pretends to feel dizzy and leans against you," he says, grinning. Sometimes the challenge of dating is part of the fun. Manal, who just married her boyfriend of two years, says a part of her misses the drama. "Our dates are so much more boring now that we are married," she says with a laugh.

Not all dates lead to marriage, of course. "You are always hoping you will find the right one," admits Yousuf, "but mostly, you just want to have fun." Besides, he says, when the time comes, his parents will pick a suitable wife for him. "Families should protect their daughters. If they flirt with boys, they probably aren't the kind of girls you want to marry."

Your Reputation Counts

Today's Saudi Arabia is a world Jane Austen would recognize. Marriages are as much about finding mates as they are about forging family alliances. A young bride is expected to have a spotless reputation; loitering too long with a boy in public can scar her chances at making a good match. It used to be that a girl's virginity was the most important thing, but today, when virginity can be cosmetically resurrected with a quick trip to Beirut or Europe, reputation is paramount. Prospective parents-in-law can demand to scrutinize a girl's mobile-phone records to ensure she hasn't had a prior relationship. For that reason, some more-affluent Saudis, with their parents' permission, choose to date outside the country. They flock to Beirut, Paris or London, where they can meet other eligible Saudis without fear of repercussions back home.

Sex, though rare, does happen. So taboo is sex outside marriage that few singles have access to contraception. If a girl gets pregnant, her family will often force a marriage. Another drawback to clandestine dating, says one Saudi psychologist, is that young women are not taught that they have the right to say no. "So she falls into rape very easily. And then she falls into the spiral of 'I lost my virginity. What am I going to do, and who will marry me?' The psychological turmoil is horrendous."

The strict segregation of genders often leads to same-sex experimentation, according to one university student. Like porn, it is for some a religiously acceptable alternative to the greater sin of fornication, particularly if it happens between young women. "The most precious thing is a girl's virginity," says al-Oweardi. "If she has relationships with her female friends, that is O.K. — it is only temporary."

For their part, many young Saudi men postpone marriage until they have a decent job. With an 11% official unemployment rate, however, that's becoming more difficult. In any event, says Ahmad al-Shugairi, a Saudi televangelist who focuses on youth issues, such thinking is out of sync with biology and a culture that emphasizes chastity. The No. 1 preoccupation with young men everywhere is sex, he says. But unlike in the U.S., where it's socially O.K. to date, Saudi "society and religion [are] saying you cannot release that desire unless you are married, which these days can be as late as 30. So what are we expecting to happen from the age of 14 to 30? It's a bomb waiting to explode, and all that the clerics can tell them is that they need to fast." He proposes that the age of marriage be lowered to better mesh with biology.

Dating, even if it goes no further than a peck on the cheek at the end of the day, serves as a pressure valve, says Salman, my would-be beau in the Chrysler. When he's waiting for his phone to ring after a night out numbering, he's not thinking about sex so much as that dopamine hit that presages potential love. If there were other, more natural ways of meeting girls, he and his friends would be less likely to engage in such aggressive behavior. He wistfully talks about Jidda, where folks go to loosen their headscarves a little. "In Jidda, you can meet girls at the café or at the beach," he says. "It's so much more normal."

Of course, by Saudi standards, Jidda is anything but normal. There, at the numerous private beach colonies lining the coast, young men and women from Saudi Arabia's "velvet class" — the upwardly mobile intelligentsia — play beach volleyball and share a hubble-bubble as the sun goes down. But as one of the young volleyball players points out, just because men and women have a little more freedom to meet in Jidda, it doesn't mean love is any closer to hand. "At my age, I am starting to worry about getting married," says 28-year-old Roua, who runs her own promotions company. "But I have to marry someone I love, and that's not easy to find." That's true in Saudi Arabia, and everywhere else.