The Living is Easy For now. The beach is a popular gathering place for the residents of Kozhikode, still a busy gateway for Kerala

'Qaliqut in Mulaybar is visited by vessels from China, Sumatra, Ceylon, the Maldives, Yemen and Fars, and in it gather merchants from all quarters ... We entered the harbour in great pomp, the like of which I have never seen in those lands, but it was bound to be a joy to be followed by distress.'

The port where Ibn Battuta made his grand entrance still welcomes the wide wooden vessels that have plied the Indian Ocean trade for centuries. The boats, called urus, carry construction material instead of coir and spices, and Malabar is now part of the Indian state of Kerala. But the old Calicut harbor is still a symbol of the free exchange of people, goods and ideas that lies at the heart of Kerala's culture.

That tradition of openness goes back to at least the 4th century, when a Syrian Christian merchant arrived in Calicut and was welcomed with a land grant by a Hindu king. Then, in the 7th century, Arab traders inspired a Hindu king to travel to Mecca, where he converted to Islam and became the legendary founding father of Kerala's Muslims. The tradition endured into the 20th century, as Malayalis — people from Kerala are called Malayalis, after their language, Malayalam — joined a new global wave of migrants.

My own Syrian Christian family went to the U.S. in the 1970s, the same time that many Muslims left for Saudi Arabia, Bahrain and Abu Dhabi. They sent money home, propping up a sleepy rural economy, and by the late 1980s, Kerala had achieved first-world health standards and near universal literacy. In 1995 the environmentalist Bill McKibben tried to explain "the enigma of Kerala." He marveled, "Not even the diversity of its population — 60% Hindu, 20% Muslim, 20% Christian, a recipe for chronic low-grade warfare in the rest of India — has stood in its way."

My own Syrian Christian family went to the U.S. in the 1970s, the same time that many Muslims left for Saudi Arabia, Bahrain and Abu Dhabi. They sent money home, propping up a sleepy rural economy, and by the late 1980s, Kerala had achieved first-world health standards and near universal literacy. In 1995 the environmentalist Bill McKibben tried to explain "the enigma of Kerala." He marveled, "Not even the diversity of its population — 60% Hindu, 20% Muslim, 20% Christian, a recipe for chronic low-grade warfare in the rest of India — has stood in its way."

Yet as Ibn Battuta predicted, joy has been followed by distress. The dark currents swirling around the Indian Ocean have brought a new cycle of change to Kerala. Security experts have warned for years that migrants to the Persian Gulf were taking extremist ideology home. The wake-up call came in October 2008, when four young Malayalis were killed by Indian security forces in an alleged jihadi training camp in Kashmir. Last July a different threat emerged when a group of young Muslims cut off the hand of a Christian professor, condemning him for writing an exam question they said insulted the Prophet Muhammad.

How did these islands of radicalism take shape in a place that was once a model of tolerance and prosperity? To find out, I traveled through Malabar, the heart of Kerala's Muslim community, interviewing religious conservatives, political activists and the families of men accused of waging holy war. The extremists, of course, are a tiny minority, but their ideology has taken root, fed on the growing disaffection of those left out of Kerala's economic and social miracle.

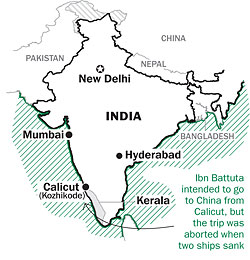

Paths to Anger

Heading north along the Kerala coast from Calicut (now called Kozhikode) to Kannur, the roads are dominated by billboards advertising gold jewelry and silk saris and by construction crews building new houses — all the visible signs of wealth from the Gulf. Kannur is where the four men who were killed in Kashmir began their journey. Indian authorities say they made 10 calls to Kerala before they were killed. A yearlong investigation, beginning with those calls, led to charges against 24 people. Police say the four men were taken to Kashmir via safe houses in Hyderabad and New Delhi by the Pakistan-based militant group Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT), whose operatives, investigators assert, directed their activities from Pakistani Kashmir and funded them with money channeled from Oman. (The Indians also blame LeT for the November 2008 assault on Mumbai.)