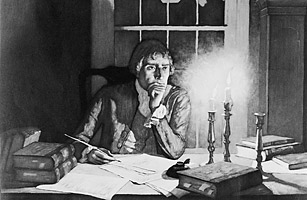

In 1801, Thomas Jefferson decided that the President's speech ought no longer be dictated before Congress and instead simply submitted it in writing in a dispatch carried by aides. The act of making the address, after all, bore unwanted similarities to the British monarch's speech from the throne, and Jefferson — his ownership of slaves notwithstanding — was known for his irrepressible democratic idealism. Historians suggest the act of submitting a written statement to Congress, rather than grandiosely uttering it, invested a kind of egalitarian simplicity into the proceedings. It also conveniently shielded the President from the howls and heckling of his many opponents.