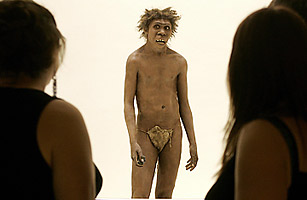

Tourists visiting the Museum for Prehistory in Eyzies-de-Tayac look at a Neanderthal man

Correction Appended: May 8, 2010

A decade after scientists first cracked the human genome, researchers announced in the May 7 issue of Science that they have done the same for Neanderthals, the species of hominid that existed from roughly 400,000 to 30,000 years ago, when their closest relatives, early modern humans, may have driven them to extinction.

Led by ancient-DNA expert Svante Pääbo of Germany's Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, scientists reconstructed about 60% of the Neanderthal genome by analyzing tiny chains of ancient DNA extracted from bone fragments of three female Neanderthals excavated in the late 1970s and early '80s from a cave in Croatia. The bones are 38,000 to 44,000 years old.

The genetic information turned up some intriguing findings, indicating, for instance, that at some point after early modern humans migrated out of Africa, they mingled and mated with Neanderthals, possibly in the Middle East or North Africa as much as 80,000 years ago. If that is the case, it occurred significantly earlier than scientists who support the interbreeding hypothesis would have expected.

Comparisons with DNA from modern humans show that some Neanderthal DNA has survived to the present. Moreover, by analyzing ancient DNA alongside modern samples, the team was able to identify a handful of genetic changes that evolved in modern humans sometime after their ancestors and Neanderthals diverged, 440,000 to 270,000 years ago.

The process of sequencing was painstaking. Among the challenges were eliminating bacterial and fungal DNA, which accounted for 97% of the genetic material in the samples, and guarding against contamination from the researchers, whose DNA might be mistaken for Neanderthals'. Plus, the DNA was so fragmented that the chains were often no longer than 40 or 50 base pairs. "We used half a gram of bones to produce the 3 billion base pairs," Pääbo said in a May 5 press conference. "I really thought until six or seven years ago that it would remain impossible, at least for my lifetime, to sequence the entire genome." New sequencing technologies made it feasible, he said.

Researchers compared the Neanderthal genome with the genomes of five living people: one San from southern Africa, one Yoruba from West Africa, one Papua New Guinean, one Han Chinese and one French person. Scientists discovered that 1% to 4% of the latter three DNA samples is shared with Neanderthals — proof that Neanderthals and early modern humans interbred. The absence of Neanderthal DNA in the genomes of the two present-day Africans indicates that interbreeding occurred after some root population of early modern humans left Africa but before the species evolved into distinct groups in Europe and Asia.

The gene flow of Neanderthal DNA into early human DNA was found in only one direction: from Neanderthals to us. The study found no early modern human DNA in the Neanderthal genome. It is not clear whether interbreeding happened a few times among small populations or frequently among large populations; the genetic remnants would look the same with current technology. The Neanderthal DNA appears in the modern human genomes randomly, suggesting it offers no evolutionary benefit and is merely a genetic relic.

Finding any mixture of DNA was a surprise to the team. "We came into the project extremely biased against the idea of gene flow," said Harvard Medical School's David Reich, one of the study's authors, who specializes in examining the relationship between human populations using genomic data.