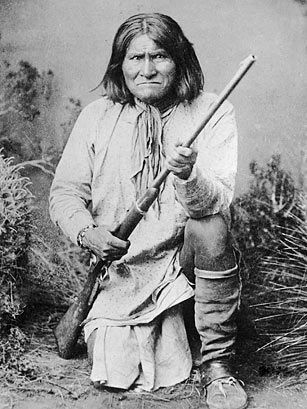

It's a strange fate that the bones of one of America's most fearful enemies have come to define one of its most hallowed institutions of power. The Apache warlord Geronimo, part guerrilla, part shaman, launched raids across the Southwest and harried and evaded U.S. and Mexican troops for nearly three decades until his capture in 1886.

But, as the story goes, the legendary rebel was not allowed to lie in peace after his death in U.S. captivity in 1909: six members of Yale's Skull and Bones secret society, including Prescott Bush, grandfather of 43rd President George W. Bush, allegedly dug up Geronimo's grave while serving as army volunteers in Oklahoma during World War I. A letter written by one of the members of the society in 1918 was brought to light by a New Haven–based researcher four years ago: "The skull of the worthy Geronimo the Terrible," it read, "exhumed from its tomb at Fort Sill by your club ... is now safe inside the tomb together with his well worn femurs, bit and saddle horn."

The second "tomb" mentioned presumably refers to the society's windowless, red stone edifice in New Haven. A flurry of lawsuits to retrieve Geronimo's skull followed, but have been deflected by the Skull and Bones, which denies possession of the Apache's remains. It still can't ward off campus rumors of the skull appearing in the society's nocturnal initiation rites, staring hollowly at the future rulers of the nation whose expansion he fought so fiercely.